By Ben Adam Climer and Brenton Gicker

From the January 2021 edition of Psychiatric Times

Download PDF

CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) is a mobile crisis-intervention program that was created in 1989 as a collaboration between White Bird Clinic and the City of Eugene, Oregon. Its mission is to improve the city’s response to mental illness, substance abuse, and homelessness.

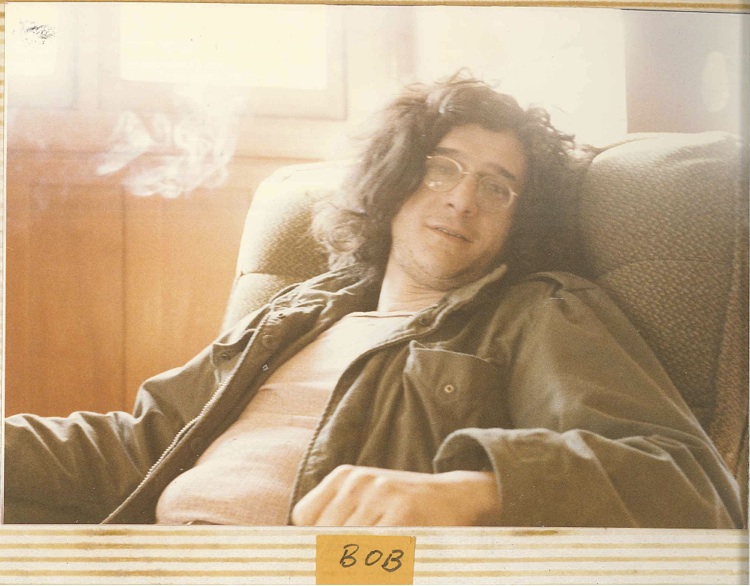

CAHOOTS is operated by White Bird Clinic, which was formed in 1969 by members of the 1960s countercultural movement. They were interested in alternative and experimental approaches to addressing societal problems. Today, White Bird Clinic operates more than a dozen programs, primarily serving low-in-come and indigent clientele.

The CAHOOTS model was developed through discussions with the city government, police department, fire department, emergency medical services (EMS), mental health department, and others. The name CAHOOTS is based on the irony of White Bird Clinic’s alternative, countercultural staff collaborating with law enforcement and mainstream agencies for the common good.

Photo by William “Bill” Holderfield

When it began, CAHOOTS had very limited availability in Eugene. It has grown into a 24-hour service in 2 cities, Eugene and Springfield, with multiple vans running during peak hours in Eugene. The program—which now responds to more than 65 calls per day—has more than quadrupled in size during the past decade due to societal needs and the increasing popularity of the program.

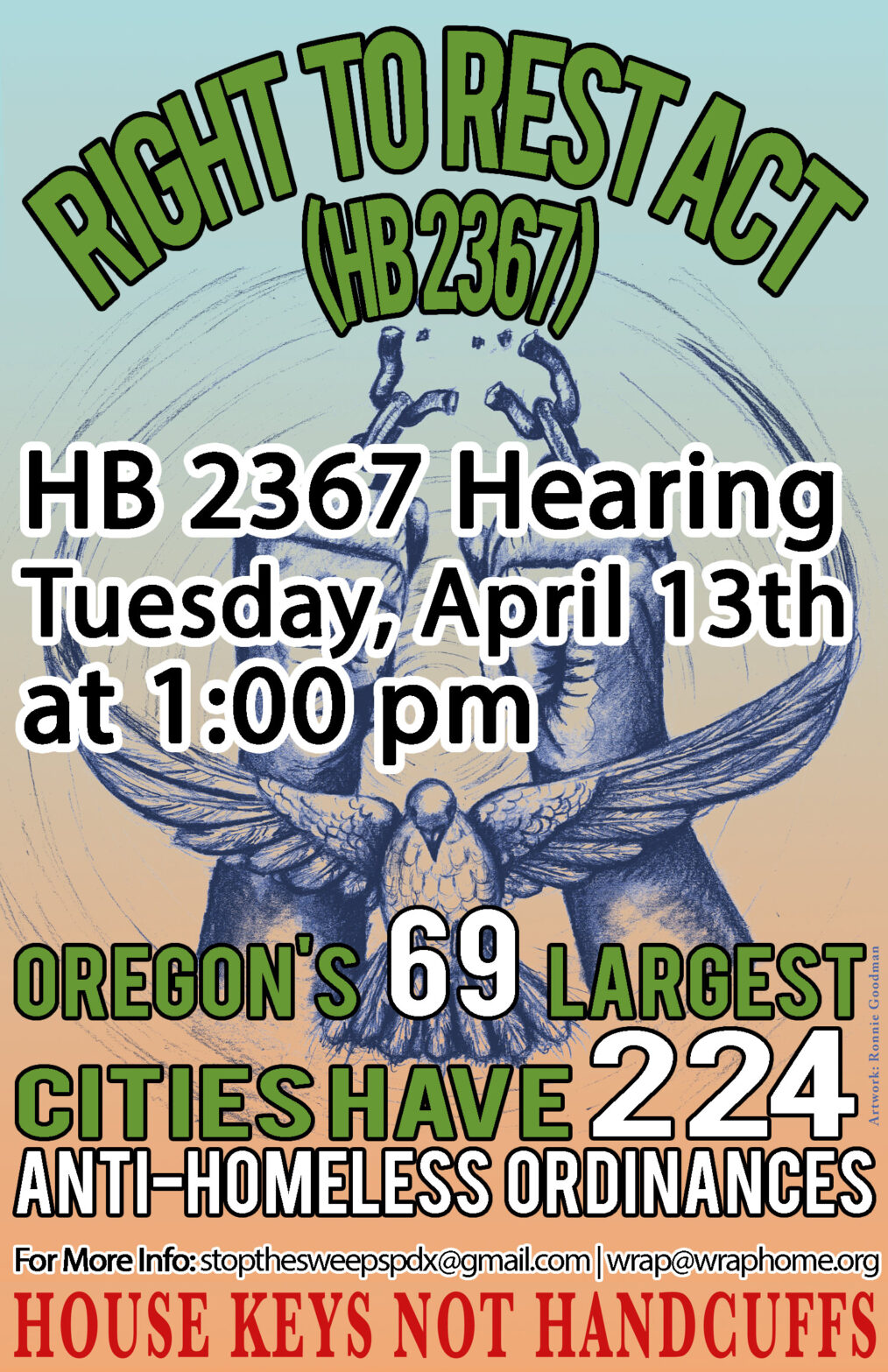

Programs based on the CAHOOTS model are being launched in numerous cities, including Denver, Oakland, Olympia, Portland, and others. Federal legislation could mandate states to create CAHOOTS-style programs in the near future.

Senators Ron Wyden of Oregon and Catherine Cortez Masto of Nevada have proposed a bill that would give states $25 million to establish or build up existing programs.

How Does It Work?

When CAHOOTS was formed, the Eugene police and fire departments were a single entity called the Department of Public Safety. CAHOOTS was designed to be a hybrid service capable of handling noncriminal, nonemergency police and medical calls, as well as other requests for service that are not clearly criminal or medical.

Eugene’s police and fire departments eventually split. CAHOOTS was absorbed into the police department’s budget and dispatch system. It continues to respond to requests typically handled by police and EMS with its integrated health care model.

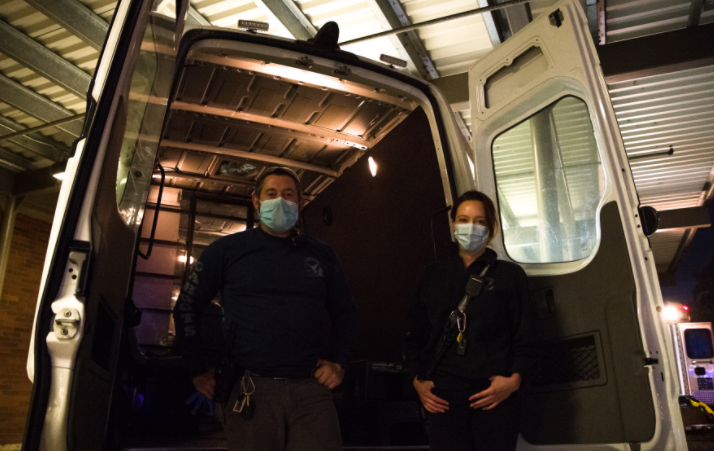

CAHOOTS operates with teams of 2: a crisis intervention worker who is skilled in counseling and deescalation techniques, and a medic who is either an EMT or a nurse. This pairing allows CAHOOTS teams to respond to a broad range of situations. For example, if an individual is feeling suicidal and they cut themselves, is the situation medical or psychiatric? Obviously, it is both, and CAHOOTS teams are equipped to address both issues. Typically, such a call involving an individual who engaged in self-harm would result in a response from police and EMS. This over-response is rarely necessary. It can also be costly and intimidating for the patient. They are not criminals, and their wounds are often not serious enough to require more than basic first aid in the field. These patients are usually seeking help, and a CAHOOTS team is trained to address both the emotional and physical needs of the patient while alleviating the need for police and EMS involvement. If necessary, CAHOOTS can transport patients to facilities such as the emergency department, crisis center, detox center, or shelter free of charge.

CAHOOTS is contacted by police dispatchers. If you call the nonemergency police line or 911 in the cities of Eugene or Springfield, you can request CAHOOTS for a broad range of problems, including mental health crises, intoxication, minor medical needs, and more. Dispatchers also route certain police and EMS calls to CAHOOTS if they determine that is appropriate.

CAHOOTS, to a large extent, operates as a free, confidential, alternative or auxiliary to police and EMS. Those services are overburdened with psych-social calls that they are often ill-equipped to handle. CAHOOTS staff rely on their persuasion and deescalation skills to manage situations, not force. Only in rare cases do CAHOOTS staff request police or EMS to transport patients against their will.

Photo by William “Bill” Holderfield

A Backup Plan

If a psychiatrist or other mental health provider in the Eugene/Springfield area is concerned about a patient, they can call CAHOOTS for assistance. This usually results in a welfare check.

Let us say, hypothetically, that you are concerned about a patient with bipolar disorder. After a lengthy period of stability, they have been complaining to you that they feel like their prescribed medication is no longer working effectively. You begin receiving phone messages and emails from them consisting of fanatical rantings and incoherent gibberish.

You are concerned, but it is not so severe that you feel compelled to call the police. Perhaps you are reluctant to call law enforcement for a variety of reasons. What do you do? You call CAHOOTS.

Having responded to a similar scenario recently, let me describe what occurred. The patient, although not expecting us, welcomed our response. They explained to us that they felt like their medication was ineffective, and, after days of mania, they were feeling depressed and suicidal.

The patient recognized their own decompensation, and eagerly accepted transport to the hospital. Their mental health care provider was informed that we were transporting them and called the hospital to provide additional information.

We transported the patient to the hospital, and they were admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit for stabilization. Collaboration between prehospital, hospital, and outpatient services facilitated that incident as smoothly as possible.

Barriers and How to Help

Prehospital mental health crisis response is underdeveloped. Most often, police and EMS are the only options. In some cities, clinicians with masters or doctoral degrees are sent with first responders. Unfortunately, the supply of these clinicians is not enough to meet the demand, but does it need to? Ambulances do not staff medical doctors. Why should prehospital mental health care require masters/doctoral level licensed clinicians? Telepsychiatry services, while important, are no substitute for direct human contact, especially given that some patients will need to be transported to a higher level of care and many do not have the means or ability to participate in telehealth services (because of lack of capacity or lack of resources).

The biggest barrier to CAHOOTS-style mobile crisis expansion is the belief that without licensed clinicians and police, prehospital mental health assistance is ineffective and unsafe. If psychiatrists want a program like this in their area, they can help by using their considerable authority to assure the community that response teams like CAHOOTS can work. Because of their direct lines of communication to the police and familiarity with police procedures, CAHOOTS staff are able to respond to high acuity mental health crisis scenarios in the field beyond what is typically allowed for mental health service providers, which often facilitates positive outcomes and can even prevent deadly outcomes. Their support is vital for program success.

Mr. Climer worked for CAHOOTS as a crisis worker for 5 years and an EMT for 2.5 of those years. He now lives in Pasadena, CA where he helps Southern California cities develop CAHOOTS-style programs. Mr. Gicker is a registered nurse and emergency medical technician who has worked for CAHOOTS since 2008.