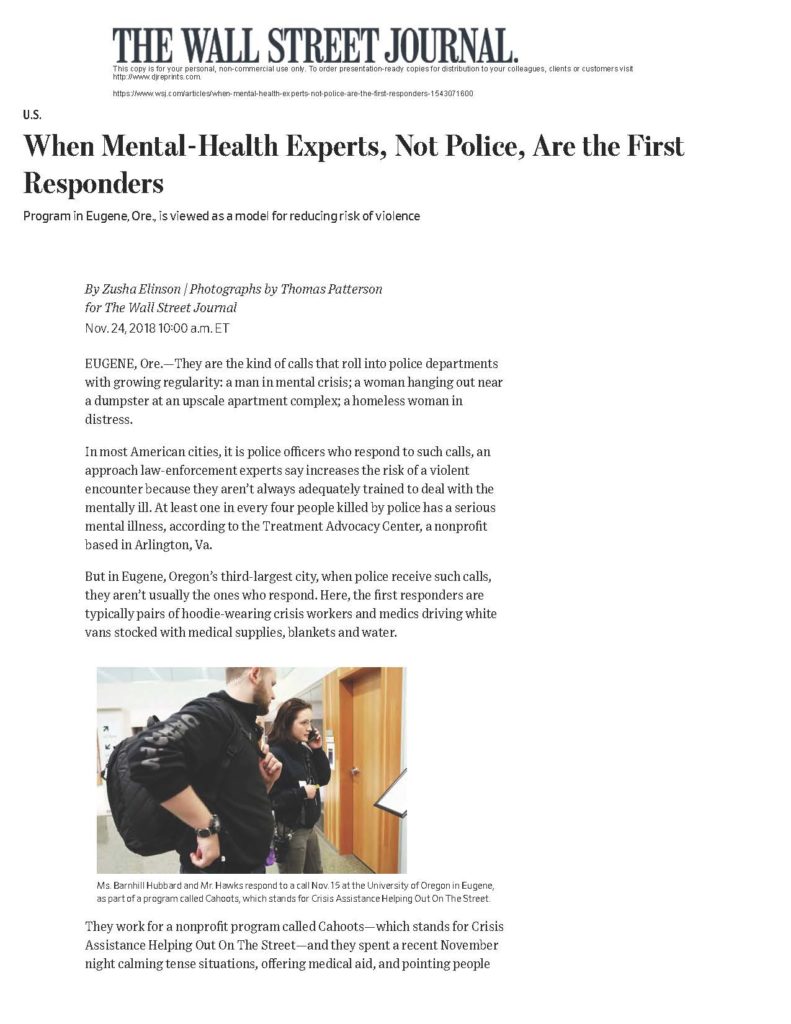

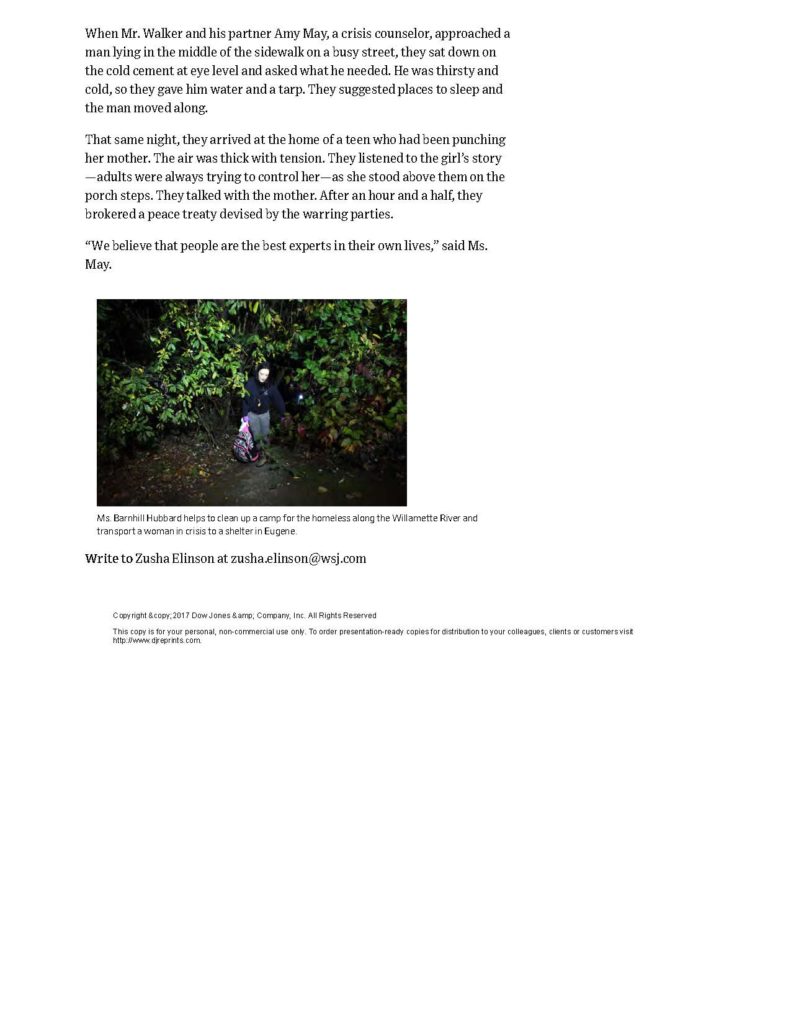

White Bird Executive Coordinator Miles Mabray (front) stands with Fund Developer, Chris Hecht, in front of the dental and medical clinic currently serving 2,000 low-income patients annually.

CREDIT TIFFANY ECKERT, KLCC

EUGENE, OREGON – White Bird Clinic will purchase the building at 1415 Pearl St. and redevelop it into a dental clinic to serve burgeoning community need. The existing dental facilities at 1400 Mill St will be renovated to add urgent care services to White Bird’s medical clinic.

The new building will allow White Bird dental to serve 50 additional patients each week and increase capacity to host student internships. The clinic will also provide denture care for elderly patients and allow White Bird to serve more children and families. White Bird medical’s new urgent care services will provide an alternative to hospital emergency room visits for patients experiencing an acute issue who lack health insurance.

“With the increase in community need for affordable urgent and preventative dental care, we’ve been on the lookout for a larger facility to better serve clients. When this opportunity came up, we knew we had to move on it immediately,” White Bird Dental Program Coordinator Kim Freuen said.

Founded in 1995, the dental clinic provides urgent care as well as preventative care. The program has continuously grown and is now constrained by its 23 year-old facility, and is not operating at optimal capacity due to a shortage of space. This year to date, the dental clinic has provided 4,848 visits for 1,992 patients:

- 829 for emergency care;

- 1,322 for hygiene/preventative care; and

- 2,697 for restorative care.

According to Trillium Community Health Plan, many of their patients don’t ever see a dentist. The last two Community Health Improvement Plans for Lane County identified affordable dental care as a major issue. Poor oral health presents significant challenges for many unhoused community members; White Bird recognizes that need and meets it.

White Bird Medical Clinic provides affordable and friendly medical care to indigent, homeless, low-income, and otherwise marginalized populations, such as community members who are employed but uninsured or underinsured. In addition to staff physicians, there is a behavioral health consultant and a psychiatric prescriber who collaborate with the physicians to offer integrated, holistic care. This year to date, the medical clinic has provided 2,226 visits for 950 patients. 1,020 of those visits were with unhoused patients.

Providing primary care to patients is crucially important, as White Bird’s patients often suffer from multiple complex medical issues that are compounded by socioeconomic barriers to health care and lifestyle changes. These community members face significant barriers as well as discrimination when attempting to access health care institutions in the community, and having White Bird primary care providers advocate for them and coordinate their care is vital.

The new medical urgent care service will divert a great number of emergency room visits, which are very costly for all stakeholders. White Bird Clinic is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

Donate

Please support our efforts by making a donation in person, by mail, or online through our website.

In the News