Responding to someone in crisis can be difficult, and knowing someone is suicidal can be scary, especially when we’re not sure how to respond. For many of us, our natural reactions to crisis can quickly escalate a situation and make things worse. That’s why professional crisis workers seek out training and practice crisis intervention strategies so that they’re prepared to navigate a crisis situation and offer support. When we develop a plan for offering support in crisis situations, it is more likely we will not go into crisis ourselves when assisting someone.

Often, for those experiencing suicidal thoughts, help can be as simple as having someone to talk to. For many, social isolation, history of trauma, mental health issues, or belonging to historically oppressed groups can lead to periods of suicidal ideation. But how do you know if someone is experiencing suicidal ideation? Often there may be signs of suicidal thoughts or behaviors.

Some warning signs of suicidal ideation can include:

- Threatening to hurt or kill oneself

- Seeking access to means to hurt or kill oneself

- Talking, thinking or writing about death, dying or suicide

- Increased use of alcohol or drugs

- Withdrawing from family, friends or society

- Showing rage or talking about seeking revenge, appearing agitated or angry

- Talking about feeling empty, hopeless, or having no reason to live, or being a burden to others

- Making a plan or looking for a way to kill themselves, such as searching online, stockpiling pills, or buying a gun

- Talking about great guilt or shame

- Feeling unbearable pain (emotional pain or physical pain)

- Acting recklessly or engaging in risky activities that could lead to death, such as driving extremely fast

- Giving away important possessions

If these warning signs apply to you or someone you know, get help as soon as possible, particularly if the behavior is new or has increased recently. Suicidal ideation is complex and there is no single cause, people of all genders, ages, and ethnicities can be at risk. In fact, many different factors contribute to someone making a suicide attempt. But people most at risk tend to share certain characteristics known as risk factors.

Often, family and friends are the first to recognize the warning signs of suicidal ideation and can be the first to assist in reaching out and getting help. Showing someone who may be experiencing a crisis that you care can make a world of difference in their life. Know how to start the conversation. Know how to ask, “Are you suicidal?” Know how to say, “I’m here for you,” and really mean it. Be aware of resources available in your community like the White Bird Crisis Line, CAHOOTS Mobile Crisis Services or the Help Book.

Risk Factors vs. Protective Factors

Characteristic and attribute that reduce the likelihood of attempting or completing suicide are known as Protective Factors. They are skills, strengths, or resources that help people deal more adequately with stressful events. Protective Factors enhance resilience and help to counterbalance Risk Factors.

Protective Factors:

- Effective clinical care for mental, physical, and substance abuse disorders

- Easy access to a variety of clinical interventions and support for help seeking

- Family and community support (connectedness)

- Support from ongoing medical and mental health care relationships

- Skills in problem solving, conflict resolution, and nonviolent ways of handling disputes

- Cultural and religious beliefs that discourage suicide and support instincts for self-preservation

Risk factors impact our ability to manage high stress situations. Being aware of these factors can assist if you are in crisis or helping someone in crisis.

Risk Factors:

- Being exposed to others’ suicidal behavior, such as that of family members, peers, or celebrities

- Depression, other mental disorders, or substance abuse disorder

- Certain medical conditions

- Chronic pain

- A prior suicide attempt

- Family history of a mental disorder or substance abuse

- Family history of suicide

- Family violence, including physical or sexual abuse

- Having guns or other firearms in the home

- Having recently been released from prison or jail

Suicidal thoughts can come on at any time like a tidal wave. Like a tidal wave, suicidal thoughts can leave a wake of destruction in their path. It is important for someone experiencing these strong thoughts and emotions to have an anchor during one these episodes. Suicidal ideation can make it seem like death is the only way out in that moment. Our rational mind may not be able to see any other solution when amid suicidal ideation. If we can help someone ride out the wave until they receive professional help, the likelihood of suicide is greatly reduced. Below are 10 steps to assist you in helping someone in crisis.

Ten Steps to Help a Person in Crisis

Step 1. Encourage the person to communicate with you.

Step 2. Be respectful and acknowledge the person’s feelings.

Step 3. Don’t be patronizing or judgmental.

Step 4. Never promise to keep someone’s suicidal feelings a secret.

Step 5. Offer reassurance that things can get better.

Step 6. Encourage the person to avoid alcohol and drug use.

Step 7. Remove potentially dangerous items from the person’s home, if possible.

Step 8. Encourage the person to call a suicide hotline number. You as the helper can also call.

Step 9. Encourage the person to seek professional help.

Step 10. Offer to help the person take steps to get assistance and support.

For our 24/7 CAHOOTS mobile crisis services, call the police non-emergency numbers 541-726-3714 (Springfield) and 541-682-5111 (Eugene). For our 24/7 crisis hotline, call 541-687-4000 or toll free at 1-800-422-7558.

Vox’s daily news explainer podcast featured White Bird Clinic’s CAHOOTS program, and how it has been an effective alternative to police involvement in mental health crises for 30 years.

Shout out from artist and musician David Byrne.

White Bird Clinic is proud to be a part of spreading this type of response across Oregon and the rest of the United States! Sen. Ron Wyden’s bill, if passed, will expand CAHOOTS-like programs throughout the U.S.

Press Release from Jeff Merkley, US Senator for Oregon

After Down Payment on the Policy Included in Reconciliation Relief Legislation, CAHOOTS Act Builds on Proven Models to Help Americans with Mental Illness and Enhances Medicaid Funding to States

Washington, D.C. – Senate Finance Committee Chair Ron Wyden, D-Ore., Senator Catherine Cortez Masto, D-Nev., and six senators today proposed a bill to help states adopt mobile crisis response teams that can be dispatched when a person is experiencing a mental health or substance use disorder (SUD) crisis instead of immediately involving law enforcement. The funding is provided through an enhanced federal match rate for state Medicaid programs.

“I’m proud there is a down payment on CAHOOTS in the emergency relief package moving through Congress now,” Wyden said. “Every day there are stories across the country of Americans in mental distress getting killed or mistreated because they did not receive the emergency mental health services they needed. White Bird Clinic in Eugene, Oregon has been a pioneer for years in this area, and it’s high time the CAHOOTS model is made available to states and local governments across the country. I am eager to get the down payment signed into law and continue working to get further investments in mobile crisis services made under the bill across the finish line.”

“Individuals experiencing a behavioral health crisis deserve to be treated with compassion and care by health care and social workers,”Cortez Masto said. “These professionals are extensively trained in deescalating situations and addressing mental health crises, and this legislation would help more states across the country fund mobile crisis teams. I’m hopeful that these investments in community-based crisis intervention services will be included in the final version of the current coronavirus relief package, and I’ll continue to advocate for effective, trauma-informed care for those in need.”

Earlier this month, the House Energy and Commerce Committee included a provision in its budget reconciliation language for COIVD-19 relief that makes an investment in these services by funding state Medicaid programs at an enhanced 85 percent federal match if they choose to provide qualifying community-based crisis intervention services and funding state planning grants to apply for the option. The pandemic has taken a serious toll on the mental health and wellbeing of Americans with studies showing a four-fold increase in the rates of anxiety and depressive disorders since the beginning of the pandemic.

The CAHOOTS program pioneered by Oregon’s @WhiteBirdClinic has shown us a safe and effective alternative to using law enforcement in mental health crises. I’m proposing legislation to expand this model nationwide and modernize our country’s outdated approach to crisis treatment.

— Ron Wyden (@RonWyden) February 18, 2021

The bill, the Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS) Act, grants states further enhanced federal Medicaid funding for three years to provide community-based mobile crisis services to individuals experiencing a mental health or SUD crisis. It also provides $25 million for planning grants to states and evaluations to help establish or build out mobile crisis programs and evaluate them.

Senators Jeff Merkley, D-Ore., Bob Casey, D-Pa., Tina Smith, D-Minn., Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., and Bernie Sanders, D-Vt., are co-sponsors of the CAHOOTS Act.

View this post on Instagram

A one-page summary of the bill can be found here. Legislative text can be found here.

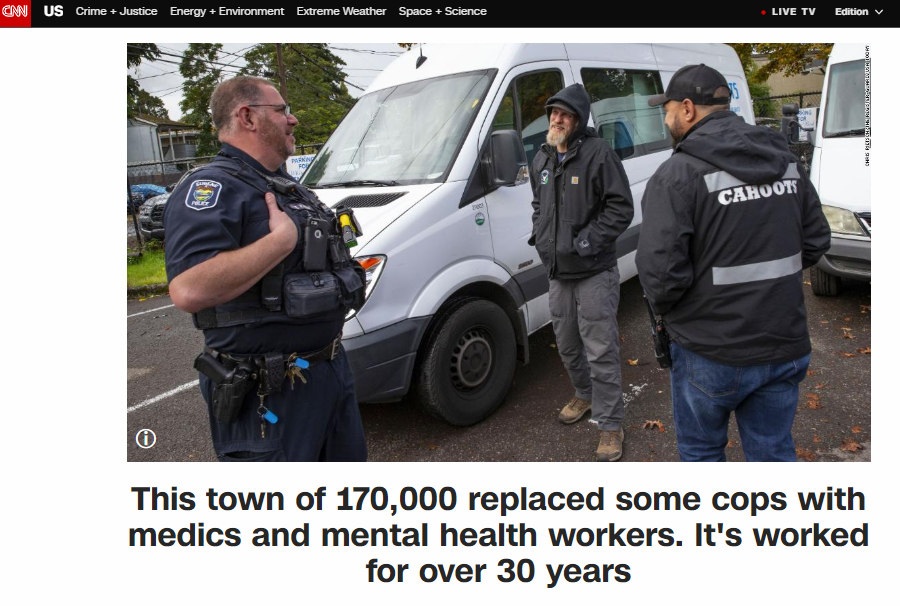

31 years ago the City of Eugene, Oregon developed an innovative community-based public safety system to provide mental health first response for crises involving mental illness, homelessness, and addiction. White Bird Clinic launched CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) as a community policing initiative in 1989.

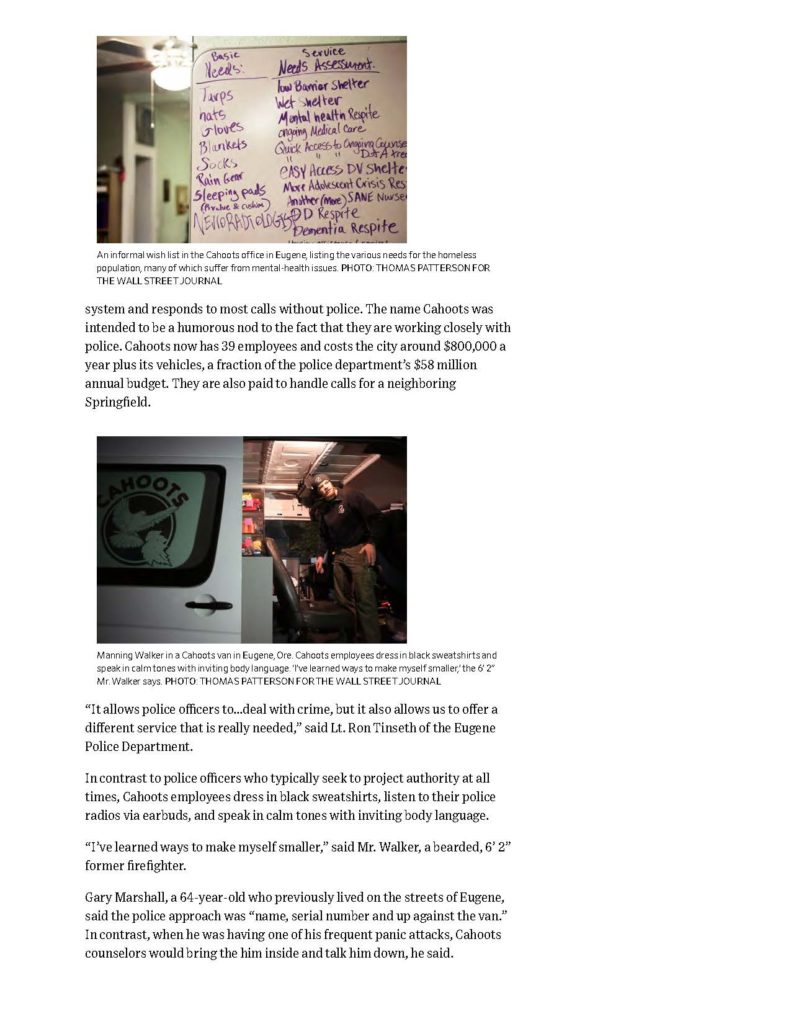

The CAHOOTS model has been in the spotlight recently as our nation struggles to reimagine public safety. The program mobilizes two-person teams consisting of a medic (a nurse, paramedic, or EMT) and a crisis worker who has substantial training and experience in the mental health field. The CAHOOTS teams deal with a wide range of mental health-related crises, including conflict resolution, welfare checks, substance abuse, suicide threats, and more, relying on trauma-informed de-escalation and harm reduction techniques. CAHOOTS staff are not law enforcement officers and do not carry weapons; their training and experience are the tools they use to ensure a non-violent resolution of crisis situations. They also handle non-emergent medical issues, avoiding costly ambulance transport and emergency room treatment.

A November 2016 study published in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine estimated that 20% to 50% of fatal encounters with law enforcement involved an individual with a mental illness. The CAHOOTS model demonstrates that these fatal encounters are not inevitable. Last year, out of a total of roughly 24,000 CAHOOTS calls, police backup was requested only 150 times.

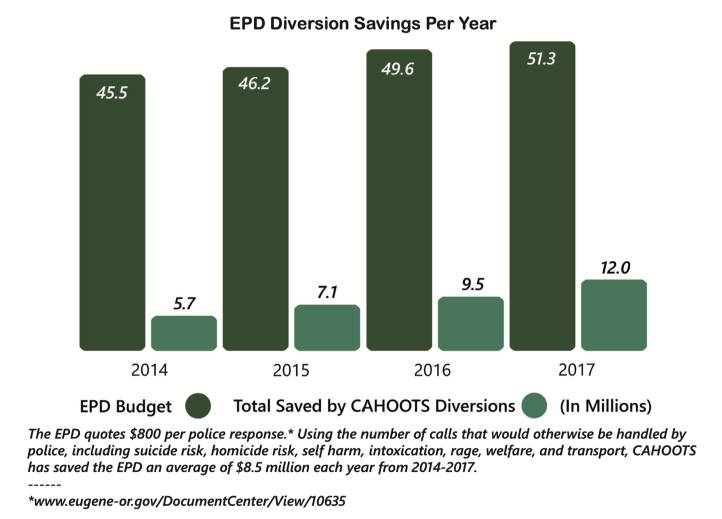

The cost savings are considerable. The CAHOOTS program budget is about $2.1 million annually, while the combined annual budgets for the Eugene and Springfield police departments are $90 million. In 2017, the CAHOOTS teams answered 17% of the Eugene Police Department’s overall call volume. The program saves the city of Eugene an estimated $8.5 million in public safety spending annually.

CAHOOTS calls come to Eugene’s 911 system or the police non-emergency number. Dispatchers are trained to recognize non-violent situations with a behavioral health component and route those calls to CAHOOTS. A team will respond, assess the situation and provide immediate stabilization in case of urgent medical need or psychological crisis, assessment, information, referral, advocacy, and, when warranted, transportation to the next step in treatment.

White Bird’s CAHOOTS provides consulting and strategic guidance to communities across the nation that are seeking to replicate CAHOOTS’ model. Contact us if you are interested in our consultation services program.

Also See:

White Bird will be participating in the “Only Way Forward” webinar series examining the impacts of Canada’s existing criminal justice system, possible alternatives, and next steps on November 12, 4-6 pm PST. Tim Black joins a panel discussion on alternative forms of policing and prisons that have been successful.

What are they and why do they work?

Panelists

Tim Black, White Bird Clinic

Tim Black is the Director of Consulting at White Bird Clinic. With a background in runaway and homeless youth, harm reduction, and street outreach, he began working for CAHOOTS as a Crisis Intervention Worker in 2010, before moving into an administrative role as the CAHOOTS Operations Coordinator.

His work with White Bird and CAHOOTS has put him in touch with cities across North America looking to implement services based on the CAHOOTS model of behavioral health first response. Programs based on the CAHOOTS model have been implemented in Olympia, Washington, and Denver, Colorado. In addition to his work with White Bird Clinic, Tim also serves as the Vice President of the Board of Directors for Eugene’s Community Supported Shelters.

Judy Cameron, Mental Health Counsellor

Judy Cameron is a member of Fort Albany First Nation and is currently living in Thunder Bay, ON. She is a mother of two and grandmother of 4 with 35 years of experience working with individuals and families in Addictions, Advocacy and Child Protection Services in a variety of settings throughout Northern Ontario. She was also a part time instructor at Confederation College in Thunder Bay, teaching classes in the Native Child and Family Worker and the Community Aboriginal Advocacy programs – the vast majority of my work has been with Indigenous children, families and communities.

Despite retiring in 2011, Judy is currently working as a mental health counsellor in Wapekeka First Nation.

“I am honoured to be a part of the Only Way Forward initiative and hope that our dialogue will bring about some meaningful change in Canadian society for the betterment of all peoples.”

Rick Kelly, Just Us : A Centre for Restorative Practices

Rick Kelly lives, as a visitor, on the traditional lands of the Anishnaabeg people. He was first introduced to the restorative model thru an indigenous lens. He has been trained by a Buddhist, rogue teacher, police officer, pastor from youth detention and Kay Pranis at the Canadian School of Peacebuilding (CMU).

He has an MA in Restorative Practices, a BA in philosophy which he was told would doom him to a short and dead-end career, and an advanced diploma in youth work. Rick works to demonstrably unhook form the legacy of the predominant justice system in order to build ecosystems that are just and equitable. This is a continuous and evolving process of understanding and development.

Around 30 years ago, a town in Oregon retrofitted an old van, staffed it with young medics and mental health counselors and sent them out to respond to the kinds of 911 calls that wouldn’t necessarily require police intervention.

by Rashida Tlaib Apr 23, 2020 in “The Appeal”

What would an Emergency First Responders Corps look like?

“The most important aspect of the Emergency First Responder Corps is that it must be civilian and designed to help people. The idea isn’t novel — it is something neighbors have been doing for centuries, and the time is now to take comprehensive approach to formalizing it to help our most vulnerable communities.

A good model of this exists in Eugene, Oregon, CAHOOTS — Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets — has worked for decades to help people in crisis. They deal with those who are suicidal, houseless, infirm, or just having trouble getting the basics they need to survive. It’s fully integrated into the local service community. And they are effective. In 2018, CAHOOTS responded to 24,000 calls. CAHOOTS and the White Bird Clinic were recently awarded federal funding to expand telemedicine access during the current pandemic.”

The Briefing: a new vision for first responders during the COVID-19 pandemic

CAHOOTS program coordinator Tim Black joined Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib and our self-described “biggest fan of CAHOOTS in the Rockies” Colorado State Representative Leslie Herod to discuss the CAHOOTS model and why there is a need for a behavioral health branch of public safety in communities across the nation.

Senator Ron Wyden will meet with White Bird CAHOOTS staff at CAHOOTS headquarters at 970 W 7th Ave in Eugene to discuss how this groundbreaking program can be a model for a national policing reform package and how Congress can best support the work. “The Justice in Policing Act of 2020 takes a vital first step toward accountability, and I am all in with pressing forward to achieve this legislation’s urgently needed re-focus of resources and policies,” said Sen. Wyden. Sen. Wyden co-sponsored the legislation, which would hold police accountable, change the culture of law enforcement and build trust between law enforcement and communities in Oregon and nationwide.

31 years ago White Bird Clinic launched CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) as a community policing initiative to provide mental health first response for crises involving mental illness, homelessness, and addiction. CAHOOTS offers compassionate, effective, timely care while diverting a considerable portion of the public safety workload, conserving police and fire department capacity. In 2019, CAHOOTS handled 17% of the Eugene Police Department’s calls. In 2017, police officers nationally spent 21% of their time responding to or transporting people with mental illness.

Dispatching appropriate responders for each unique situation is essential to ensuring the best outcome. CAHOOTS focuses exclusively on meeting the medical and mental health needs of the community, making it more appropriate, economical, and effective than traditional models involving agencies with a much larger scope of responsibility.

Police officers and fire fighters receive training in a broad set of skills, making their deployment to non-emergent situations unnecessarily costly. The CAHOOTS model also ensures that health and behavioral health care are integrated from the onset of intervention and treatment, adding to the efficacy and economy of the model.

White Bird’s CAHOOTS program has attracted notice from international news media as communities across the nation and around the world confront the need to reimagine public safety to ensure that it equitably serves human beings of all races and ethnicities.

CAHOOTS is providing strategic guidance and training to assist communities in developing innovative public safety systems that align with their values.

In 1969, a group of student activists and concerned practitioners came together to provide crisis services and free medical care for counter-culture youth in Eugene, OR. Having grown continuously since then, today White Bird Clinic has 10 programs, 220 staff members, and more than 400 volunteers each year.

In The Appeal‘s Explainer series, Justice Collaborative lawyers, journalists, and other legal experts help unpack some of the most complicated issues in the criminal justice system.

Co-authors Tim Black, CAHOOTS Operations Coordinator, and Patrisse Cullors, Artist and Activist, “break down the problems behind the headlines—like bail, civil asset forfeiture, or the Brady doctrine—so that everyone can understand them. Wherever possible, we try to utilize the stories of those affected by the criminal justice system to show how these laws and principles should work, and how they often fail.”

NPR Morning Edition took a look at effective alternatives to police response that keep people out of jails and emergency rooms. Tim Black from CAHOOTS is featured at about 7:08.

NPR’s Ari Shapiro talked with crisis workers Benjamin Brubaker and Ebony Morgan at White Bird Clinic in Eugene, Ore., about their Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets program as an alternative to police intervention. Read the transcript…

The National, a nightly news program from Canada’s public broadcaster CBC, interviewed Tim Black and Ebony Morgan from CAHOOTS about our alternative model to police intervention for crisis response.

White Bird Clinic’s CAHOOTS program is meeting with stakeholders to share an innovative model for mobile crisis intervention that would otherwise be handled by public safety or emergency medical response.

OAKLAND, CA – White Bird Clinic of Eugene, OR has developed an innovative public/private partnership delivering crisis and community health first response effectively and at significant cost savings. For thirty years, CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) has been providing mobile crisis intervention 24/7, dispatched through the EMS non-emergency system. This week, members of CAHOOTS are in Oakland to meet with the Mayor, the Coalition for Police Accountability, and other community stakeholders to discuss implementing the innovative model locally.

Each CAHOOTS team consists of a medic (a nurse or an EMT) with a crisis worker who has substantial training and experience in the mental health field. The team provides behavioral health first response/responders, immediate stabilization in case of urgent medical need or psychological crisis, assessment, information, referral, advocacy and, when warranted, transportation to the next step in treatment.

White Bird Clinic started CAHOOTS in 1989 in partnership with the Eugene Police Department as a community policing initiative. CAHOOTS offers compassionate, effective, timely care while diverting a considerable portion of the public safety workload, freeing the police and fire departments to respond to the highest priority calls. CAHOOTS handles 17% of the Eugene Police Department’s non-emergency calls. In 2017, police officers nationally spent 21% of their time responding to or transporting people with mental illness.

CAHOOTS focuses exclusively on meeting the medical and mental health needs of the community, making it both more economical and more effective than traditional models involving agencies with a larger scope of responsibility. Police officers and firefighters receive comprehensive training in a broad set of skills, making their deployment to non-emergent situations unnecessarily costly. The CAHOOTS model also ensures that health and behavior health care are integrated from the onset of intervention and treatment, adding to the efficacy and economy of the model.

White Bird’s CAHOOTS program has attracted notice, from national news media as well as from communities across the country. The Wall Street Journal’s November 24th article When Mental- Health Experts, Not Police, Are the First Responders showcased CAHOOTS as an innovative model for reducing the risk of violent civilian/police encounters. Communities from California to New York have asked for strategic guidance and training so they can replicate CAHOOTS’ success.

Currently, CAHOOTS is working with the following communities:

- Olympia, WA

- Portland, OR

- Denver, CO

- New York, NY

- Indianapolis, IN

- Roseburg, OR

In 1969, a group of student activists and concerned practitioners came together to provide crisis services and free medical care for counter-culture youth in Eugene, OR. Having grown continuously since then, today White Bird Clinic has 10 programs, 220 staff members, and more than 400 volunteers each year. White Bird Clinic is a collective environment organized to empower people to gain control of their social, emotional, and physical well-being through direct service, education, and community.

The mission of the Coalition for Police Accountability is to advocate for accountability of the Oakland Police Department to the community so that the Oakland Police Department operates with equitable, just, constitutional, transparent policies and practices that reflect the values and engender the trust of the community.

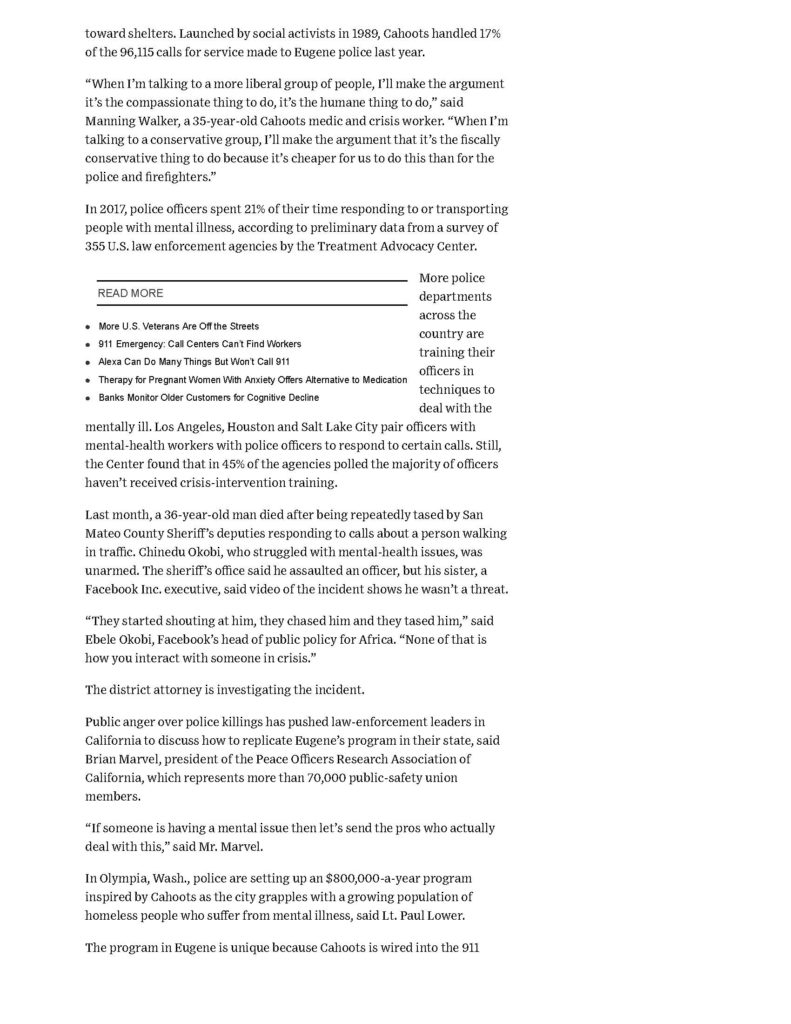

Kaia Sands, Executive Director of Street Roots, a Portland newspaper that creates income opportunities for people experiencing homelessness and poverty through media that is a catalyst for individual and social change, visited White Bird Clinic’s mobile crisis support program, CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) this month.

In 2019, Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler, Police Chief Danielle Outlaw and Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty’s staff have all come to Eugene to learn about the CAHOOTS model response to non-criminal matters resulting from homelessness. Kaia joined our crisis worker and medic team for a shift and shared her story, available in PDF for download here with permission.

Street Roots visit to CAHOOTS helped to inform their plan for a Portland Street Response team. This would be a non-law enforcement system of six well-marked mobile response vans teamed with a specially-trained firefighter-EMT and peer support specialist dispatched through both 911 and nonemergency channels. Street Roots explores how these issues are being responded to in Portland and Eugene and how we can build a better system. Read more (PDF)…

I write in my column for tomorrow’s @StreetRoots that Eugene’s CAHOOTS @WhiteBirdClinic takes many of those “unwanted person” calls. So can #PortlandStreetResponse. People need help, not criminal enforcement.

— Kaia Sand (@mkaiasand) March 15, 2019

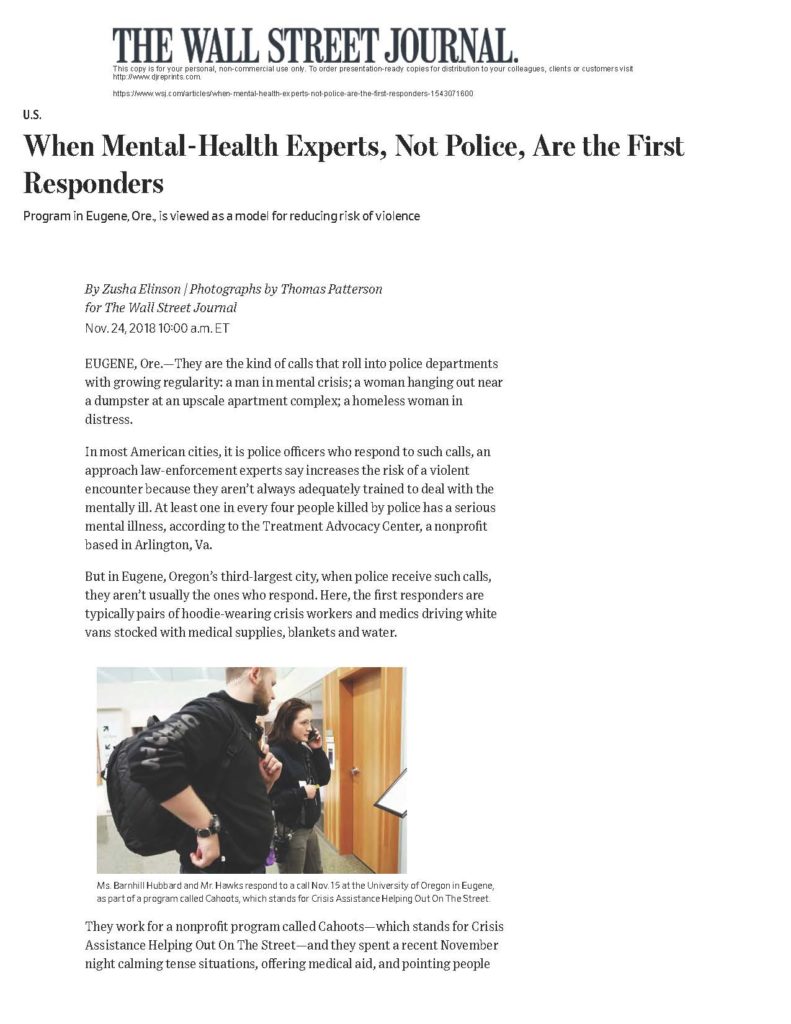

The Wall Street Journal featured CAHOOTS as a model for reducing risk of violence in a November 24, 2018 article by Zusha Elinson.

It is included below and as a PDF with permission from the publisher.

The CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) program began in Eugene in 1989 as a collaboration between the city of Eugene and White Bird Clinic.

CAHOOTS started small: one van equipped with medical supplies and trained personnel, operating part-time in Eugene. Its mission was simple: to offer help to individuals and families, housed and unhoused, in crisis.

The idea was that it would be better — and cheaper — to have people trained and experienced in counseling and medical care to respond to these calls, which had been going to police and fire departments.

The wisdom of that decision has been amply borne out since then by CAHOOTS’ exponential growth over the last three decades and the place it has made for itself in the Eugene-Springfield community.

It has more than tripled its local presence with two vans in Eugene and one in Springfield, and gone from part-time patrols to 24-7 service.

The two-person teams that staff each van respond to an average of about 15 to 16 calls in a 12-hour shift in Eugene, although it can be as many as 25 calls per shift — slightly less in Springfield, CAHOOTS employee Brenton Gicker says, which works out to tens of thousands of calls per year.

Gicker is a registered nurse and emergency medical technician; his partner on a recent night, Maddy Slayden, is a paramedic.

They and their co-workers are a welcome presence on the streets of Eugene-Springfield, greeted with warmth by police officers, with relief by business owners who prefer the option of calling CAHOOTS to calling police, and with respect by the people they help.

CAHOOTS is a significant part of the network of organizations and agencies that provide help to the growing number of people who are homeless locally — about half of CAHOOTS’ calls are to help someone who is homeless, ranging in age from children to seniors.

The CAHOOTS teams have earned respect in the homeless community not just for the help they provide — from distributing socks and bottles of water to emergency medical care and help accessing resources such as medical treatment and emergency shelter — but by the way they do it.

The CAHOOTS employees offer dignity and courtesy, which are often in short supply for people who are homeless.

A typical shift — if there were such a thing — for a CAHOOTS team might include responding to a call about a homeless person disrupting a business; working with a family in crisis; helping someone who is suffering from substance abuse, mental illness or developmental disabilities access services and find safe shelter for the night; treating injuries; picking up people who are being discharged from a hospital or clinic with no place to go and taking them to a safe place where they can get help; and responding to a call from a landlord worried about the welfare of a tenant.

They are trained to address issues such as mental illness or substance abuse and skilled in coaxing people to agree to get the help they need.

Many of their calls involve driving people who are suffering from mental illness or substance abuse to an emergency

room or, if their problem doesn’t merit medical care, to a safe place to spend the night.

Despite more than tripling the size of CAHOOTS in the past few years, the need for its services continues to grow faster than CAHOOTS’ resources.

“I’m frustrated because we can’t be everywhere at once,” Gicker says. “There’s always things we’d like to be involved in, sometimes we don’t have the resources we need, or access to information. I feel like we’re often only scratching the surface.”

CAHOOTS is a uniquely local response to local needs — people familiar with the program say they don’t know of anything quite like it elsewhere.

Its growth in recent years has shown the need for its service; the response within the community, its ability to meet them given the resources.

It’s time to start thinking about expanding a program that has been successful and that serves a need that continues to grow.

Ideally, adding another van would be a step toward meeting this growing need, as well as allowing expansion of service to areas such as Santa Clara and Goshen that have few resources. It also would allow CAHOOTS staff to respond more quickly to calls seeking help, reach more people who are in need of help, and spend more time working to connect people with the resources they need.

It’s hard to put a dollar value on what CAHOOTS does — how do you determine, for example, how many people didn’t die on the streets because of CAHOOTS? How many people who were able to get help that allowed them to stabilize their lives, or medical care that relieved suffering? How do you quantify exactly how much taxpayer money was saved by using CAHOOTS instead of police or firefighters, or the value to businesses of knowing they can call CAHOOTS for help?

But the role the CAHOOTS teams play in Lane County is a critical one, and likely to become even more critical in the coming years.

This editorial is part of a Register-Guard series focusing on productive responses to homelessness reposted with permission from http://registerguard.com/rg/opinion/36272835-78/helping-people-in-crisis.html.csp