Remembering Bob Dritz, A White Bird Clinic Original

By TIFFANY ECKERT • JAN 27, 2017

http://klcc.org/post/remembering-bob-dritz-white-bird-clinic-original

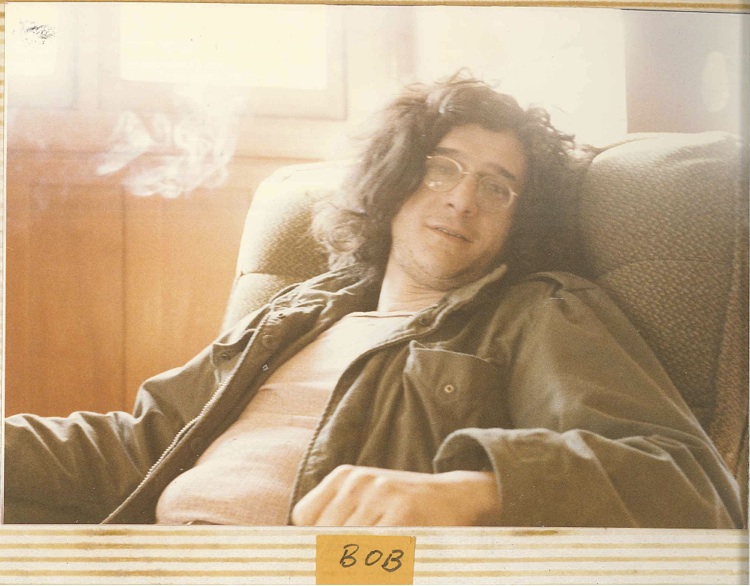

Friends, family and countless members of Eugene’s homeless community have lost a tireless advocate. Robert “Bob” Dritz, one of the earliest administrators of White Bird Clinic, died peacefully in hospice on January 15th. For this tribute, KLCC’s Tiffany Eckert sat down with two of his colleagues at White Bird to talk about the man and his legacy.

Bob Dritz was born in Bronxville, New York in 1946, the big brother of three sisters. He suffered from asthma as a child, a condition that often kept him inside. Friends say this is what developed his lifelong love of books.

Dritz went to college and taught English for a time. In the late ’70s, he eschewed work in California finance and lit out to find his real purpose. Dritz found it here, at Eugene’s White Bird Clinic, a fledgling non-profit agency dedicated to helping the poor, sick and disenfranchised.

Cori Taggart first met Bob Dritz while on a tour for new White Bird volunteers in 1979. The future crisis counselor remembers what she saw:

Wry smile: “These round glasses and a twinkle in his eye and this wry smile–he kinda gave us a wave as we walked through and I said to myself, ‘That is a very interesting looking man.”

The two later became intimate partners and then after that, they remained close.

Taggart: “He really respected women for their intelligence, their independence. He would never make cracks about a woman’s body or anything like that. That was just not him. When really smart women said something, he didn’t need to outdo them.”

At White Bird, Dritz quickly went from bookkeeper to program coordinator. Taggart recalls how he once handled a threat to cut crisis funding.

Taggart: “He showed up at that meeting with a phone book. When it was his turn to speak, he said ‘I want to speak to the importance of this crisis line to our community.’ He opened the phone book and on the front page with all the other emergency numbers was White Bird Crisis. The funding was restored.”

Not interested in the trappings of leadership, Dritz developed an equitable pay structure at White Bird that kept administration square in the middle. For more than a decade, Dee Hall worked with him.

Hall says Dritz was always humble, in attitude and dress. He usually wore jeans and a tee shirt to work.

Hall: “But his concession to being the public spokesman for White Bird was to take the cinnamon colored leather jacket off the back of the admin door.”

And then there was his memorable head of black hair, often tucked under a straw hat.

Hall: “For those of you who knew Bobby, it was amazing. Before he went out to a meeting, he grabbed the hairbrush out of his desk and he would brush his hair very carefully. And then he would put his hand over it and mix it like an egg beater. He reveled in the tussled look.”

Taggart: “Walking into a meeting of county commissioners or important people of some sort…you know he might have a simple little bag while other people would have these beautiful leather briefcases, sharp suits and great ties and everything. But when Bob opened his mouth, they started to listen.”

Friends and colleagues will miss Bob Dritz’s wry sense of humor. After creating White Bird’s mobile crisis unit, Hall says he decided on the acronym CAHOOTS.

Hall: “Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Street, the joke behind that one is that as an old hippie agency, suddenly we were in cahoots with the police. It was a surprise to all of us.”

In 2007, after 25 years of service, Bob Dritz retired from the clinic he helped build. Hall says, Dritz was deeply committed to the collective nature of White Bird.

Hall:”So we would often talk about how can we remain a collective and do the work that’s needed in the community. That structure continues and even with the new generation of White Birders, be believed we’d be able to keep the magic going into the next generation.”

The agency is now synonymous with crisis counseling, medical, dental, and drug and alcohol treatment for people living in poverty or on the streets.

In early January, Bob Dritz developed a blood infection. Codi Taggart was with him when he decided to stop treatment. She sat at his bedside and thanked him for everything.

Taggart: “He looked at me and he nodded and he said, ‘I gave it my all.’ And he did.”

Bob Dritz would have turned 71 on February 5th, 2017. A lover of the arts, poetry and a fan of Bob Dylan if ever there was one.