Press Release from Jeff Merkley, US Senator for Oregon

After Down Payment on the Policy Included in Reconciliation Relief Legislation, CAHOOTS Act Builds on Proven Models to Help Americans with Mental Illness and Enhances Medicaid Funding to States

Washington, D.C. – Senate Finance Committee Chair Ron Wyden, D-Ore., Senator Catherine Cortez Masto, D-Nev., and six senators today proposed a bill to help states adopt mobile crisis response teams that can be dispatched when a person is experiencing a mental health or substance use disorder (SUD) crisis instead of immediately involving law enforcement. The funding is provided through an enhanced federal match rate for state Medicaid programs.

“I’m proud there is a down payment on CAHOOTS in the emergency relief package moving through Congress now,” Wyden said. “Every day there are stories across the country of Americans in mental distress getting killed or mistreated because they did not receive the emergency mental health services they needed. White Bird Clinic in Eugene, Oregon has been a pioneer for years in this area, and it’s high time the CAHOOTS model is made available to states and local governments across the country. I am eager to get the down payment signed into law and continue working to get further investments in mobile crisis services made under the bill across the finish line.”

“Individuals experiencing a behavioral health crisis deserve to be treated with compassion and care by health care and social workers,”Cortez Masto said. “These professionals are extensively trained in deescalating situations and addressing mental health crises, and this legislation would help more states across the country fund mobile crisis teams. I’m hopeful that these investments in community-based crisis intervention services will be included in the final version of the current coronavirus relief package, and I’ll continue to advocate for effective, trauma-informed care for those in need.”

Earlier this month, the House Energy and Commerce Committee included a provision in its budget reconciliation language for COIVD-19 relief that makes an investment in these services by funding state Medicaid programs at an enhanced 85 percent federal match if they choose to provide qualifying community-based crisis intervention services and funding state planning grants to apply for the option. The pandemic has taken a serious toll on the mental health and wellbeing of Americans with studies showing a four-fold increase in the rates of anxiety and depressive disorders since the beginning of the pandemic.

The CAHOOTS program pioneered by Oregon’s @WhiteBirdClinic has shown us a safe and effective alternative to using law enforcement in mental health crises. I’m proposing legislation to expand this model nationwide and modernize our country’s outdated approach to crisis treatment.

— Ron Wyden (@RonWyden) February 18, 2021

The bill, the Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS) Act, grants states further enhanced federal Medicaid funding for three years to provide community-based mobile crisis services to individuals experiencing a mental health or SUD crisis. It also provides $25 million for planning grants to states and evaluations to help establish or build out mobile crisis programs and evaluate them.

Senators Jeff Merkley, D-Ore., Bob Casey, D-Pa., Tina Smith, D-Minn., Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., and Bernie Sanders, D-Vt., are co-sponsors of the CAHOOTS Act.

View this post on Instagram

A one-page summary of the bill can be found here. Legislative text can be found here.

By Ben Adam Climer and Brenton Gicker

From the January 2021 edition of Psychiatric Times

CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) is a mobile crisis-intervention program that was created in 1989 as a collaboration between White Bird Clinic and the City of Eugene, Oregon. Its mission is to improve the city’s response to mental illness, substance abuse, and homelessness.

CAHOOTS is operated by White Bird Clinic, which was formed in 1969 by members of the 1960s countercultural movement. They were interested in alternative and experimental approaches to addressing societal problems. Today, White Bird Clinic operates more than a dozen programs, primarily serving low-in-come and indigent clientele.

The CAHOOTS model was developed through discussions with the city government, police department, fire department, emergency medical services (EMS), mental health department, and others. The name CAHOOTS is based on the irony of White Bird Clinic’s alternative, countercultural staff collaborating with law enforcement and mainstream agencies for the common good.

Photo by William “Bill” Holderfield

When it began, CAHOOTS had very limited availability in Eugene. It has grown into a 24-hour service in 2 cities, Eugene and Springfield, with multiple vans running during peak hours in Eugene. The program—which now responds to more than 65 calls per day—has more than quadrupled in size during the past decade due to societal needs and the increasing popularity of the program.

Programs based on the CAHOOTS model are being launched in numerous cities, including Denver, Oakland, Olympia, Portland, and others. Federal legislation could mandate states to create CAHOOTS-style programs in the near future.

Senators Ron Wyden of Oregon and Catherine Cortez Masto of Nevada have proposed a bill that would give states $25 million to establish or build up existing programs.

How Does It Work?

When CAHOOTS was formed, the Eugene police and fire departments were a single entity called the Department of Public Safety. CAHOOTS was designed to be a hybrid service capable of handling noncriminal, nonemergency police and medical calls, as well as other requests for service that are not clearly criminal or medical.

Eugene’s police and fire departments eventually split. CAHOOTS was absorbed into the police department’s budget and dispatch system. It continues to respond to requests typically handled by police and EMS with its integrated health care model.

CAHOOTS operates with teams of 2: a crisis intervention worker who is skilled in counseling and deescalation techniques, and a medic who is either an EMT or a nurse. This pairing allows CAHOOTS teams to respond to a broad range of situations. For example, if an individual is feeling suicidal and they cut themselves, is the situation medical or psychiatric? Obviously, it is both, and CAHOOTS teams are equipped to address both issues. Typically, such a call involving an individual who engaged in self-harm would result in a response from police and EMS. This over-response is rarely necessary. It can also be costly and intimidating for the patient. They are not criminals, and their wounds are often not serious enough to require more than basic first aid in the field. These patients are usually seeking help, and a CAHOOTS team is trained to address both the emotional and physical needs of the patient while alleviating the need for police and EMS involvement. If necessary, CAHOOTS can transport patients to facilities such as the emergency department, crisis center, detox center, or shelter free of charge.

CAHOOTS is contacted by police dispatchers. If you call the nonemergency police line or 911 in the cities of Eugene or Springfield, you can request CAHOOTS for a broad range of problems, including mental health crises, intoxication, minor medical needs, and more. Dispatchers also route certain police and EMS calls to CAHOOTS if they determine that is appropriate.

CAHOOTS, to a large extent, operates as a free, confidential, alternative or auxiliary to police and EMS. Those services are overburdened with psych-social calls that they are often ill-equipped to handle. CAHOOTS staff rely on their persuasion and deescalation skills to manage situations, not force. Only in rare cases do CAHOOTS staff request police or EMS to transport patients against their will.

Photo by William “Bill” Holderfield

A Backup Plan

If a psychiatrist or other mental health provider in the Eugene/Springfield area is concerned about a patient, they can call CAHOOTS for assistance. This usually results in a welfare check.

Let us say, hypothetically, that you are concerned about a patient with bipolar disorder. After a lengthy period of stability, they have been complaining to you that they feel like their prescribed medication is no longer working effectively. You begin receiving phone messages and emails from them consisting of fanatical rantings and incoherent gibberish.

You are concerned, but it is not so severe that you feel compelled to call the police. Perhaps you are reluctant to call law enforcement for a variety of reasons. What do you do? You call CAHOOTS.

Having responded to a similar scenario recently, let me describe what occurred. The patient, although not expecting us, welcomed our response. They explained to us that they felt like their medication was ineffective, and, after days of mania, they were feeling depressed and suicidal.

The patient recognized their own decompensation, and eagerly accepted transport to the hospital. Their mental health care provider was informed that we were transporting them and called the hospital to provide additional information.

We transported the patient to the hospital, and they were admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit for stabilization. Collaboration between prehospital, hospital, and outpatient services facilitated that incident as smoothly as possible.

Barriers and How to Help

Prehospital mental health crisis response is underdeveloped. Most often, police and EMS are the only options. In some cities, clinicians with masters or doctoral degrees are sent with first responders. Unfortunately, the supply of these clinicians is not enough to meet the demand, but does it need to? Ambulances do not staff medical doctors. Why should prehospital mental health care require masters/doctoral level licensed clinicians? Telepsychiatry services, while important, are no substitute for direct human contact, especially given that some patients will need to be transported to a higher level of care and many do not have the means or ability to participate in telehealth services (because of lack of capacity or lack of resources).

The biggest barrier to CAHOOTS-style mobile crisis expansion is the belief that without licensed clinicians and police, prehospital mental health assistance is ineffective and unsafe. If psychiatrists want a program like this in their area, they can help by using their considerable authority to assure the community that response teams like CAHOOTS can work. Because of their direct lines of communication to the police and familiarity with police procedures, CAHOOTS staff are able to respond to high acuity mental health crisis scenarios in the field beyond what is typically allowed for mental health service providers, which often facilitates positive outcomes and can even prevent deadly outcomes. Their support is vital for program success.

Mr. Climer worked for CAHOOTS as a crisis worker for 5 years and an EMT for 2.5 of those years. He now lives in Pasadena, CA where he helps Southern California cities develop CAHOOTS-style programs. Mr. Gicker is a registered nurse and emergency medical technician who has worked for CAHOOTS since 2008.

31 years ago the City of Eugene, Oregon developed an innovative community-based public safety system to provide mental health first response for crises involving mental illness, homelessness, and addiction. White Bird Clinic launched CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) as a community policing initiative in 1989.

The CAHOOTS model has been in the spotlight recently as our nation struggles to reimagine public safety. The program mobilizes two-person teams consisting of a medic (a nurse, paramedic, or EMT) and a crisis worker who has substantial training and experience in the mental health field. The CAHOOTS teams deal with a wide range of mental health-related crises, including conflict resolution, welfare checks, substance abuse, suicide threats, and more, relying on trauma-informed de-escalation and harm reduction techniques. CAHOOTS staff are not law enforcement officers and do not carry weapons; their training and experience are the tools they use to ensure a non-violent resolution of crisis situations. They also handle non-emergent medical issues, avoiding costly ambulance transport and emergency room treatment.

A November 2016 study published in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine estimated that 20% to 50% of fatal encounters with law enforcement involved an individual with a mental illness. The CAHOOTS model demonstrates that these fatal encounters are not inevitable. Last year, out of a total of roughly 24,000 CAHOOTS calls, police backup was requested only 150 times.

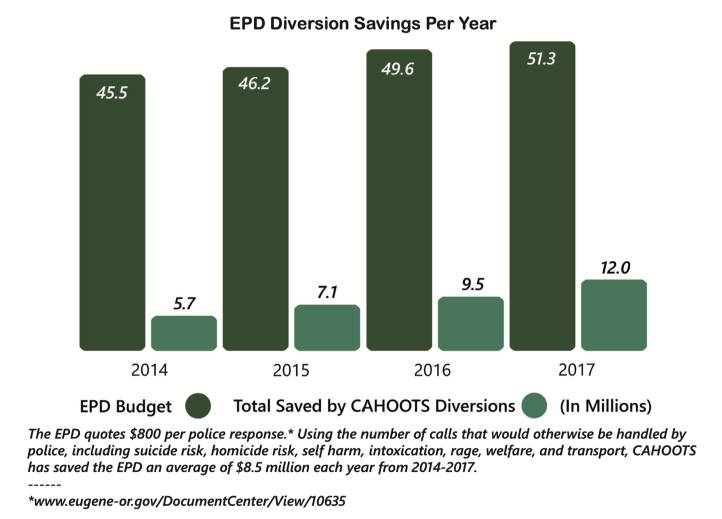

The cost savings are considerable. The CAHOOTS program budget is about $2.1 million annually, while the combined annual budgets for the Eugene and Springfield police departments are $90 million. In 2017, the CAHOOTS teams answered 17% of the Eugene Police Department’s overall call volume. The program saves the city of Eugene an estimated $8.5 million in public safety spending annually.

CAHOOTS calls come to Eugene’s 911 system or the police non-emergency number. Dispatchers are trained to recognize non-violent situations with a behavioral health component and route those calls to CAHOOTS. A team will respond, assess the situation and provide immediate stabilization in case of urgent medical need or psychological crisis, assessment, information, referral, advocacy, and, when warranted, transportation to the next step in treatment.

White Bird’s CAHOOTS provides consulting and strategic guidance to communities across the nation that are seeking to replicate CAHOOTS’ model. Contact us if you are interested in our consultation services program.

Also See:

Around 30 years ago, a town in Oregon retrofitted an old van, staffed it with young medics and mental health counselors and sent them out to respond to the kinds of 911 calls that wouldn’t necessarily require police intervention.

by Rashida Tlaib Apr 23, 2020 in “The Appeal”

What would an Emergency First Responders Corps look like?

“The most important aspect of the Emergency First Responder Corps is that it must be civilian and designed to help people. The idea isn’t novel — it is something neighbors have been doing for centuries, and the time is now to take comprehensive approach to formalizing it to help our most vulnerable communities.

A good model of this exists in Eugene, Oregon, CAHOOTS — Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets — has worked for decades to help people in crisis. They deal with those who are suicidal, houseless, infirm, or just having trouble getting the basics they need to survive. It’s fully integrated into the local service community. And they are effective. In 2018, CAHOOTS responded to 24,000 calls. CAHOOTS and the White Bird Clinic were recently awarded federal funding to expand telemedicine access during the current pandemic.”

The Briefing: a new vision for first responders during the COVID-19 pandemic

CAHOOTS program coordinator Tim Black joined Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib and our self-described “biggest fan of CAHOOTS in the Rockies” Colorado State Representative Leslie Herod to discuss the CAHOOTS model and why there is a need for a behavioral health branch of public safety in communities across the nation.

Senator Ron Wyden will meet with White Bird CAHOOTS staff at CAHOOTS headquarters at 970 W 7th Ave in Eugene to discuss how this groundbreaking program can be a model for a national policing reform package and how Congress can best support the work. “The Justice in Policing Act of 2020 takes a vital first step toward accountability, and I am all in with pressing forward to achieve this legislation’s urgently needed re-focus of resources and policies,” said Sen. Wyden. Sen. Wyden co-sponsored the legislation, which would hold police accountable, change the culture of law enforcement and build trust between law enforcement and communities in Oregon and nationwide.

31 years ago White Bird Clinic launched CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) as a community policing initiative to provide mental health first response for crises involving mental illness, homelessness, and addiction. CAHOOTS offers compassionate, effective, timely care while diverting a considerable portion of the public safety workload, conserving police and fire department capacity. In 2019, CAHOOTS handled 17% of the Eugene Police Department’s calls. In 2017, police officers nationally spent 21% of their time responding to or transporting people with mental illness.

Dispatching appropriate responders for each unique situation is essential to ensuring the best outcome. CAHOOTS focuses exclusively on meeting the medical and mental health needs of the community, making it more appropriate, economical, and effective than traditional models involving agencies with a much larger scope of responsibility.

Police officers and fire fighters receive training in a broad set of skills, making their deployment to non-emergent situations unnecessarily costly. The CAHOOTS model also ensures that health and behavioral health care are integrated from the onset of intervention and treatment, adding to the efficacy and economy of the model.

White Bird’s CAHOOTS program has attracted notice from international news media as communities across the nation and around the world confront the need to reimagine public safety to ensure that it equitably serves human beings of all races and ethnicities.

CAHOOTS is providing strategic guidance and training to assist communities in developing innovative public safety systems that align with their values.

In 1969, a group of student activists and concerned practitioners came together to provide crisis services and free medical care for counter-culture youth in Eugene, OR. Having grown continuously since then, today White Bird Clinic has 10 programs, 220 staff members, and more than 400 volunteers each year.

In The Appeal‘s Explainer series, Justice Collaborative lawyers, journalists, and other legal experts help unpack some of the most complicated issues in the criminal justice system.

Co-authors Tim Black, CAHOOTS Operations Coordinator, and Patrisse Cullors, Artist and Activist, “break down the problems behind the headlines—like bail, civil asset forfeiture, or the Brady doctrine—so that everyone can understand them. Wherever possible, we try to utilize the stories of those affected by the criminal justice system to show how these laws and principles should work, and how they often fail.”

NPR Morning Edition took a look at effective alternatives to police response that keep people out of jails and emergency rooms. Tim Black from CAHOOTS is featured at about 7:08.

NPR’s Ari Shapiro talked with crisis workers Benjamin Brubaker and Ebony Morgan at White Bird Clinic in Eugene, Ore., about their Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets program as an alternative to police intervention. Read the transcript…

The National, a nightly news program from Canada’s public broadcaster CBC, interviewed Tim Black and Ebony Morgan from CAHOOTS about our alternative model to police intervention for crisis response.

White Bird’s CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) program continues to make headlines. CBS Evening News with Norah O’Donnell correspondent Omar Villafranca went on a ride-along with CAHOOTS to see them at work and learn why the program is being considered by cities across the country.

NBC News featured the team’s approach in their feature “Taking police officers out of mental health-related 911 rescues.”

Denver police officials said they are considering the model as an option to push beyond their existing co-responder program. New York City is looking to the program as “a model for non-police response to non-criminal emergencies.”

Salem nonprofits are looking at the model for mobile crisis response. “CAHOOTS gets 2 percent of the police budget, but with that 2 percent they handle 17 percent of public safety calls,” said Ashley Hamilton, who’s helping spearhead the idea.

Rogue Valley law enforcement, mental health professionals and advocates, elected officials and other concerned community members gathered at the Medford Police Department to hear Tim Black talk via Skype about the program in September. In November, city commissioners are expected to discuss how the program would work in Portland.

The power of White Bird’s CAHOOTS program lies in its community relationships and the ability of first responders to simply ask, ‘How can I support you today?’ White Bird Clinic is proud to be a part of spreading this type of response across Oregon and the rest of the United States.