‘Healing House” is an excerpt from “FRONTLINE,” a 40,000-word original work of creative nonfiction on White Bird Clinic’s crisis intervention team, published in 1994 by Mark H. Massé, who received his master’s degree with honors from the School of Journalism and Communication (SOJC) at the University of Oregon in 1994. After serving on the SOJC faculty, he spent 22 years in the Department of Journalism at Ball State University, retiring in 2018 as professor emeritus.

Copyright (1994) by Mark H. Massé. All rights reserved.

Twenty-some years ago, White Bird Clinic was known as a glorified crash pad for teenagers who were hallucinating on psychedelic drugs. The clinic, which was founded as a counterculture collective in 1970, was viewed with suspicion and concern by the Eugene establishment. People criticized its perceived. “overly permissive attitude” toward drug use. Some said White Bird was harboring criminals and runaways.

The police were angry about the clinic’s confidentiality agreements with clients whom the cops saw as drug-dealing lowlifes. A typical front-desk encounter at White Bird would go something like this:

“You can’t or won’t tell me if this guy hangs out here?” the police officer asks the long-haired receptionist. “Both,” the White Birder replies, smugly.

Today, White Bird Clinic’s confrontational image has mellowed, but it has retained its collective/communal organizational structure and its identity as a grass-roots human services and community advocacy organization. White Bird’s mission: to serve the people nobody else wants to deal with, the folks who fall between the cracks. Each year, the clinic responds to the medical, mental health, and social service needs of thousands of low-income, alienated, abandoned, and disenfranchised clients in Lane County.

Through the decades, the once-controversial clinic has transformed itself, becoming more establishment oriented than anyone could have imagined back in the 1970s. White Bird Clinic now has a million-dollar annual operating budget and is involved in cooperative programs with Sacred Heart Hospital, Lane, County Mental Health Services, and the Eugene Police Department, plus many other public- and private-sector organizations. The clinic’s comprehensive operations include medical and dental services, 24-hour crisis intervention, mental health screening and evaluation programs, AIDS testing, drug treatment services, and extensive information and referral services.

One innovative cooperative venture is C.A.H.O.O.T.S. (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets), a result of a 1989 partnership between White Bird Clinic and Eugene’s public safety system. Funded by the city of Eugene, the C.A.H.O.O.T.S. program uses a van that is radio-dispatched through the 911 system. A two-person team—a White Bird crisis worker and a trained medic—responds to calls dealing with drug and alcohol abuse, mental illness, emotional crises, and family disputes that pose a small risk of violence.

One innovative cooperative venture is C.A.H.O.O.T.S. (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets), a result of a 1989 partnership between White Bird Clinic and Eugene’s public safety system. Funded by the city of Eugene, the C.A.H.O.O.T.S. program uses a van that is radio-dispatched through the 911 system. A two-person team—a White Bird crisis worker and a trained medic—responds to calls dealing with drug and alcohol abuse, mental illness, emotional crises, and family disputes that pose a small risk of violence.

Over the years, White Bird Clinic’s clientele has also changed, becoming more representative of the mainstream community. The clinic’s crisis intervention team frequently handles calls from area residents of all ages who have questions about personal or family relationships, as well as more serious concerns such as suicide prevention, domestic abuse, or chemical dependency issues. Case in point: Recently, an 11-year-old girl from a middle-class suburb, called the clinic because her parents were going through a divorce, but they weren’t including their daughter in any discussions. The girl was referred to White Bird by a telephone operator. She later talked with a White Bird counselor about what was happening to her and her family.

“Maybe we’re more reputable today than we think we are,” says Bob Dritz, White Bird Clinic’s coordinator, as he reflects on the clinic’s rocky-road history over the last 25 years. It is as if White Bird Clinic has a Protean identity—it continues to evolve and reinvent itself in response to changes in the outside world. Dritz relishes his role as resident historian of White Bird Clinic.

“Maybe we’re more reputable today than we think we are,” says Bob Dritz, White Bird Clinic’s coordinator, as he reflects on the clinic’s rocky-road history over the last 25 years. It is as if White Bird Clinic has a Protean identity—it continues to evolve and reinvent itself in response to changes in the outside world. Dritz relishes his role as resident historian of White Bird Clinic.

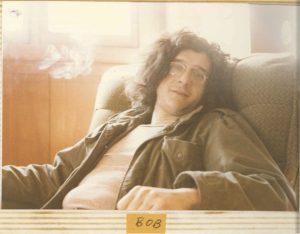

With his mop of black hair, tinted aviator-style glasses, and wide-brimmed straw hat, his rag-tag wardrobe, and laid-back crash-pad drawl, Dritz looks and sounds more like a zoned-out, middle-aged hipster than a keen-minded financial whiz who helped guide the clinic down the path to respectability. At the start of each season’s new-volunteer orientation session at White Bird, 20 individuals, who have already been screened by a clinic trainer, sit on the floor in the community room and await their introduction to the organization. Clinic coordinator Dritz sits among the newcomers like a wise tribal chief and recites the oft-told tale of White Bird Clinic.

The history of the clinic dates back to the late 1960s when the drug problem officially hit Eugene, Oregon. Disenchanted, angry, and rebellious youths roamed the streets of this bucolic city nestled in the heart of the lush Willamette Valley in western Oregon. These “hippies,” who had rejected authority and conventional lifestyles, were turning on and tuning in to a new consciousness. They were experimenting with hallucinogens, amphetamines, barbiturates, and just about any other drug they could get their hands on. LSD—”acid”—was the drug of choice for this psychedelic generation who were “tripping” to pursue psychic exploration, achieve satori (enlightenment), or get their kicks on mind-bending, reality-twisting roller-coaster rides.

The problem was that the ticket to nirvana often came at a high price. Young drug users were overdosing, taking bad trips (“bummers”) and “freaking out.” Having severed their ties with straight society, many of the drug-taking youth were without food, shelter, or proper medical care.

In the late sixties, the medical establishment in Eugene and everywhere else didn’t know how to deal with the drug problem. The emergency room doctors were, in the words of one historical account, “flying by the seat of their pants” when treating patients on bad acid trips, injecting them with high doses of phenothiazine tranquilizers, usually 50 mg of Thorazine. Thorazine was seen as a means of normalizing and sedating patients with psychotic or schizophrenic behavior, which is how the ER doctors viewed drug overdoses. The problem was that phenothiazines packed some pretty heavy side effects. A disoriented teenager on a bad trip who came into an emergency room could very well leave in worse shape than when he or she arrived—shot full of Thorazine and now suffering from dizziness, blurred vision, muscle spasms, or tremors.

In the late sixties, the medical establishment in Eugene and everywhere else didn’t know how to deal with the drug problem. The emergency room doctors were, in the words of one historical account, “flying by the seat of their pants” when treating patients on bad acid trips, injecting them with high doses of phenothiazine tranquilizers, usually 50 mg of Thorazine. Thorazine was seen as a means of normalizing and sedating patients with psychotic or schizophrenic behavior, which is how the ER doctors viewed drug overdoses. The problem was that phenothiazines packed some pretty heavy side effects. A disoriented teenager on a bad trip who came into an emergency room could very well leave in worse shape than when he or she arrived—shot full of Thorazine and now suffering from dizziness, blurred vision, muscle spasms, or tremors.

Out of the purple haze that had descended on Eugene, stepped two 25-year-old doctoral students in psychology from the University of Oregon. Dennis Ekanger and Frank Lemons looked like characters from the movie “M.A.S.H:” Here’s Ekanger—a Radar O’Reilly, with more hair. There’s Lemons, a Hawkeye Pierce/Donald Sutherland stand-in, with more hair and a beard, of course.

Ekanger knew firsthand about the problems of drug abuse from his days as a resident hall counselor at the University of Oregon and in his work as a juvenile counselor for the county. The rap on the street was that the chain-smoking, deep-voiced Ekanger was an empathetic guy who could help you cool down and sort things out. Ekanger was living in an old Victorian-style house on 20th Avenue and Lincoln in Eugene’s “student ghetto.” His reputation grew to the point where students and drifters, Vietnam vets and runaways would be hanging out on his doorstep every day wanting to rap about their mixed-up lives.

Like Dennis Ekanger, Frank Lemon had a following. For months, he had been counseling young people in crisis. Lemons’ reputation was enhanced by his counterculture connections. He had many friends living in a large commune on a 200-plus acre farm outside of town. The members of the commune would later form the core group of White Bird’s supervisors and full-time volunteers in the clinic’s early years.

In 1969, Ekanger and Lemons enlisted the support of Dr. Leonard Jacobson, a successful and respected surgeon and past president of the county’s medical society. Dr. Jacobson had been outspoken about the need for new approaches to the drug crisis. He provided the legitimacy and the established community contacts that Ekanger and Lemons lacked.

The three men conceived of a psycho-social-medical approach (influenced by such operations as the Haight Ashbury Free Clinic in San Francisco) and advanced the idea of a community free clinic and counseling/drug education center, a sanctuary to deal with people’s drug-related problems. More than 100 community leaders were involved in the crafting of the proposal for a clinic to be known officially as White Bird Sociomedical Aid Station, Inc.

Ekanger and Lemons each put up $250 to incorporate the clinic and organized a board of directors. The two served as the clinic’s co-directors. After securing grants from the city ($4,800) and state ($7,500), plus community donations, White Bird Clinic started operating on February 22, 1970, in a rented house at 837 Lincoln Street. Furniture was donated by local churches. Area hospitals contributed medical equipment and supplies. In the first few weeks, more than 150 doctors and nurses, plus dozens of attorneys, social workers, and educators donated their time and services to get the clinic up and running. After only one month, the clinic was being used as a field site for graduate students in counseling. Soon, more than 100 -university students were clinic volunteers.

In October 1971, the clinic purchased adjacent houses at 323 and 341 E. 12th Avenue for $67,500. The “annex” at 323 E. 12th housed the medical clinic and drug detox and drug education services. The clinic’s main building at 341 E. 12th was headquarters for crisis intervention, counseling, legal services, and an expanding list of client advocacy and referral programs.

The house at 341 E. 12th Avenue had once been the residence of a prominent physician who was one of the founders of the Eugene Clinic. The house was built for $4,000 in 1917 according to the specifications of Dr. Philip Bartle, a specialist in internal medicine who ran his medical practice on the main floor of the 3,500-square-foot, two-story home where he lived with his -wife and two children.

According to The History of the Willamette Valley, Oregon, published in 1927, Philip Bartle was a perfectionist, “a man among men, possessing a strong and forceful personality.” Bartle was committed to working on behalf of the public welfare for the “betterment of the community along all legitimate lines.” In the 1920s, he helped establish the Eugene Hospital and Clinic, at the time one of only two standardized hospitals in Oregon outside of Portland.

Bartle’s home was designed in the popular craftsman style of his day. This elaborate “bungalow-type” of architecture featured large porches with truncated pillars or columns, low-pitched gable-styled roofs with prominent gabled dormers, and multi-paned windows of varying shapes and sizes. The front room had extensive wood detailing—columns, beams, paneling, and window casements. Two maple window seats flanked the first-floor mantel and fireplace.

Outside, near the top of the front of the house was a decorative swastika. It was removed during World War II. By then, Dr. Bartle had moved, and the house was sold to his son, William and his wife, Mildred. During the late 1930s, several rooms were rented to University of Oregon students, a practice that continued until 1971 when Mildred Bartle sold the house to White Bird Clinic.

Outside, near the top of the front of the house was a decorative swastika. It was removed during World War II. By then, Dr. Bartle had moved, and the house was sold to his son, William and his wife, Mildred. During the late 1930s, several rooms were rented to University of Oregon students, a practice that continued until 1971 when Mildred Bartle sold the house to White Bird Clinic.

The clinic’s operations in the 1970s were a lot shakier than the sturdy structure in which they were housed. By 1972, both Dennis Ekanger and Frank Lemons had resigned. Several White Birders were arrested that year on drug charges; they were later acquitted. In October 1972, the clinic’s medical area was temporarily closed because of lack of supplies, lack of money, and lack of support from the Eugene medical community. The county’s medical society came forward to assist the clinic but told White Bird that it had to clean up its act, raise its standards, and be willing to accept outside advice on all medical matters.

Through all the clinic’s hassles in-the early years, a core of dedicated White Birders served the cause. They staffed the clinic’s drug detox program, continued round-the-clock crisis intervention services, and ran an ambitious drug education program in the community—giving frank talks to area schools, church groups, and civic organizations. They published a “Drug Education Primer,” which was distributed throughout Eugene, and they staged street “guerrilla” theater productions to raise community awareness and show the establishment where the cracks in the medical and mental health systems were.

White Bird’s topsy-turvy operations continued until the late 1970s. A soft-spoken transplanted New Yorker named Bob Dritz arrived in 1978. He became the clinic’s fiscal officer and ushered in a period of maturity and relative calm. In another life, Dritz could have been a CEO of a start-up company and made a small fortune.

White Bird’s topsy-turvy operations continued until the late 1970s. A soft-spoken transplanted New Yorker named Bob Dritz arrived in 1978. He became the clinic’s fiscal officer and ushered in a period of maturity and relative calm. In another life, Dritz could have been a CEO of a start-up company and made a small fortune.

But he used his expertise in fiscal planning and budget management to secure the future of White Bird, not make himself rich. like so many others of his generation, Dritz rejected conventional middle-class values and chose a life of community service and social activism. For his work on behalf of the clinic, Dritz gained near-legendary status. He was proclaimed the “financial savior” of the White Bird Clinic.

In July 1982, Bob Dritz assumed the role of clinic coordinator. At this point, the clinic was being recognized as a legitimate and vital link in the county’s health care system. It had an established crisis counselor training program (the Willamette School of Human Services) licensed by the state of Oregon. The clinic also had a diversified base of funding from local, county, state, and federal grants. By the end of the decade, Dritz would oversee a major expansion and diversification of clinic services.

Today, Bob Dritz talks about how the clinic continues to surprise its critics and leverage its clout as an alternative human service agency.

“We’re willing to take on assignments that no other organization wants or has the ability to perform,” Dritz says, sitting in his office on the second floor of the house with the prominent blue, white and gold bird-in-flight sign hanging above its wide front porch. Throughout its colorful history, the distinctive residence at 341 E. 12th Avenue has undergone many changes and transformations. But after 77 years, it remains a healing house for people in need in Lane County.

Massé has authored three books of literary journalism (“Vietnam Warrior Voices,” “Trauma Journalism” and “Inspired to Serve.”) He is also a novelist, whose latest work, “Honor House,” will be published on Amazon.com in summer 2020. For more information, visit: http://www.markmasse.com