Vox’s daily news explainer podcast featured White Bird Clinic’s CAHOOTS program, and how it has been an effective alternative to police involvement in mental health crises for 30 years.

White Bird Clinic is proud to be a part of spreading this type of response across Oregon and the rest of the United States! Sen. Ron Wyden’s bill, if passed, will expand CAHOOTS-like programs throughout the U.S.

By Ben Adam Climer and Brenton Gicker

From the January 2021 edition of Psychiatric Times

CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) is a mobile crisis-intervention program that was created in 1989 as a collaboration between White Bird Clinic and the City of Eugene, Oregon. Its mission is to improve the city’s response to mental illness, substance abuse, and homelessness.

CAHOOTS is operated by White Bird Clinic, which was formed in 1969 by members of the 1960s countercultural movement. They were interested in alternative and experimental approaches to addressing societal problems. Today, White Bird Clinic operates more than a dozen programs, primarily serving low-in-come and indigent clientele.

The CAHOOTS model was developed through discussions with the city government, police department, fire department, emergency medical services (EMS), mental health department, and others. The name CAHOOTS is based on the irony of White Bird Clinic’s alternative, countercultural staff collaborating with law enforcement and mainstream agencies for the common good.

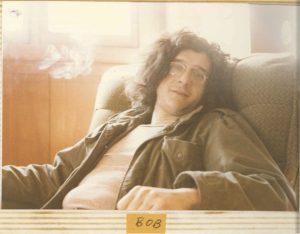

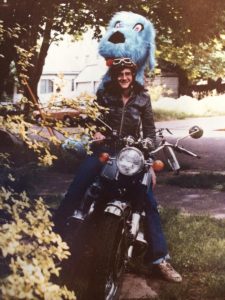

Photo by William “Bill” Holderfield

When it began, CAHOOTS had very limited availability in Eugene. It has grown into a 24-hour service in 2 cities, Eugene and Springfield, with multiple vans running during peak hours in Eugene. The program—which now responds to more than 65 calls per day—has more than quadrupled in size during the past decade due to societal needs and the increasing popularity of the program.

Programs based on the CAHOOTS model are being launched in numerous cities, including Denver, Oakland, Olympia, Portland, and others. Federal legislation could mandate states to create CAHOOTS-style programs in the near future.

Senators Ron Wyden of Oregon and Catherine Cortez Masto of Nevada have proposed a bill that would give states $25 million to establish or build up existing programs.

How Does It Work?

When CAHOOTS was formed, the Eugene police and fire departments were a single entity called the Department of Public Safety. CAHOOTS was designed to be a hybrid service capable of handling noncriminal, nonemergency police and medical calls, as well as other requests for service that are not clearly criminal or medical.

Eugene’s police and fire departments eventually split. CAHOOTS was absorbed into the police department’s budget and dispatch system. It continues to respond to requests typically handled by police and EMS with its integrated health care model.

CAHOOTS operates with teams of 2: a crisis intervention worker who is skilled in counseling and deescalation techniques, and a medic who is either an EMT or a nurse. This pairing allows CAHOOTS teams to respond to a broad range of situations. For example, if an individual is feeling suicidal and they cut themselves, is the situation medical or psychiatric? Obviously, it is both, and CAHOOTS teams are equipped to address both issues. Typically, such a call involving an individual who engaged in self-harm would result in a response from police and EMS. This over-response is rarely necessary. It can also be costly and intimidating for the patient. They are not criminals, and their wounds are often not serious enough to require more than basic first aid in the field. These patients are usually seeking help, and a CAHOOTS team is trained to address both the emotional and physical needs of the patient while alleviating the need for police and EMS involvement. If necessary, CAHOOTS can transport patients to facilities such as the emergency department, crisis center, detox center, or shelter free of charge.

CAHOOTS is contacted by police dispatchers. If you call the nonemergency police line or 911 in the cities of Eugene or Springfield, you can request CAHOOTS for a broad range of problems, including mental health crises, intoxication, minor medical needs, and more. Dispatchers also route certain police and EMS calls to CAHOOTS if they determine that is appropriate.

CAHOOTS, to a large extent, operates as a free, confidential, alternative or auxiliary to police and EMS. Those services are overburdened with psych-social calls that they are often ill-equipped to handle. CAHOOTS staff rely on their persuasion and deescalation skills to manage situations, not force. Only in rare cases do CAHOOTS staff request police or EMS to transport patients against their will.

Photo by William “Bill” Holderfield

A Backup Plan

If a psychiatrist or other mental health provider in the Eugene/Springfield area is concerned about a patient, they can call CAHOOTS for assistance. This usually results in a welfare check.

Let us say, hypothetically, that you are concerned about a patient with bipolar disorder. After a lengthy period of stability, they have been complaining to you that they feel like their prescribed medication is no longer working effectively. You begin receiving phone messages and emails from them consisting of fanatical rantings and incoherent gibberish.

You are concerned, but it is not so severe that you feel compelled to call the police. Perhaps you are reluctant to call law enforcement for a variety of reasons. What do you do? You call CAHOOTS.

Having responded to a similar scenario recently, let me describe what occurred. The patient, although not expecting us, welcomed our response. They explained to us that they felt like their medication was ineffective, and, after days of mania, they were feeling depressed and suicidal.

The patient recognized their own decompensation, and eagerly accepted transport to the hospital. Their mental health care provider was informed that we were transporting them and called the hospital to provide additional information.

We transported the patient to the hospital, and they were admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit for stabilization. Collaboration between prehospital, hospital, and outpatient services facilitated that incident as smoothly as possible.

Barriers and How to Help

Prehospital mental health crisis response is underdeveloped. Most often, police and EMS are the only options. In some cities, clinicians with masters or doctoral degrees are sent with first responders. Unfortunately, the supply of these clinicians is not enough to meet the demand, but does it need to? Ambulances do not staff medical doctors. Why should prehospital mental health care require masters/doctoral level licensed clinicians? Telepsychiatry services, while important, are no substitute for direct human contact, especially given that some patients will need to be transported to a higher level of care and many do not have the means or ability to participate in telehealth services (because of lack of capacity or lack of resources).

The biggest barrier to CAHOOTS-style mobile crisis expansion is the belief that without licensed clinicians and police, prehospital mental health assistance is ineffective and unsafe. If psychiatrists want a program like this in their area, they can help by using their considerable authority to assure the community that response teams like CAHOOTS can work. Because of their direct lines of communication to the police and familiarity with police procedures, CAHOOTS staff are able to respond to high acuity mental health crisis scenarios in the field beyond what is typically allowed for mental health service providers, which often facilitates positive outcomes and can even prevent deadly outcomes. Their support is vital for program success.

Mr. Climer worked for CAHOOTS as a crisis worker for 5 years and an EMT for 2.5 of those years. He now lives in Pasadena, CA where he helps Southern California cities develop CAHOOTS-style programs. Mr. Gicker is a registered nurse and emergency medical technician who has worked for CAHOOTS since 2008.

‘Healing House” is an excerpt from “FRONTLINE,” a 40,000-word original work of creative nonfiction on White Bird Clinic’s crisis intervention team, published in 1994 by Mark H. Massé, who received his master’s degree with honors from the School of Journalism and Communication (SOJC) at the University of Oregon in 1994. After serving on the SOJC faculty, he spent 22 years in the Department of Journalism at Ball State University, retiring in 2018 as professor emeritus.

Copyright (1994) by Mark H. Massé. All rights reserved.

Twenty-some years ago, White Bird Clinic was known as a glorified crash pad for teenagers who were hallucinating on psychedelic drugs. The clinic, which was founded as a counterculture collective in 1970, was viewed with suspicion and concern by the Eugene establishment. People criticized its perceived. “overly permissive attitude” toward drug use. Some said White Bird was harboring criminals and runaways.

The police were angry about the clinic’s confidentiality agreements with clients whom the cops saw as drug-dealing lowlifes. A typical front-desk encounter at White Bird would go something like this:

“You can’t or won’t tell me if this guy hangs out here?” the police officer asks the long-haired receptionist. “Both,” the White Birder replies, smugly.

Today, White Bird Clinic’s confrontational image has mellowed, but it has retained its collective/communal organizational structure and its identity as a grass-roots human services and community advocacy organization. White Bird’s mission: to serve the people nobody else wants to deal with, the folks who fall between the cracks. Each year, the clinic responds to the medical, mental health, and social service needs of thousands of low-income, alienated, abandoned, and disenfranchised clients in Lane County.

Through the decades, the once-controversial clinic has transformed itself, becoming more establishment oriented than anyone could have imagined back in the 1970s. White Bird Clinic now has a million-dollar annual operating budget and is involved in cooperative programs with Sacred Heart Hospital, Lane, County Mental Health Services, and the Eugene Police Department, plus many other public- and private-sector organizations. The clinic’s comprehensive operations include medical and dental services, 24-hour crisis intervention, mental health screening and evaluation programs, AIDS testing, drug treatment services, and extensive information and referral services.

One innovative cooperative venture is C.A.H.O.O.T.S. (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets), a result of a 1989 partnership between White Bird Clinic and Eugene’s public safety system. Funded by the city of Eugene, the C.A.H.O.O.T.S. program uses a van that is radio-dispatched through the 911 system. A two-person team—a White Bird crisis worker and a trained medic—responds to calls dealing with drug and alcohol abuse, mental illness, emotional crises, and family disputes that pose a small risk of violence.

One innovative cooperative venture is C.A.H.O.O.T.S. (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets), a result of a 1989 partnership between White Bird Clinic and Eugene’s public safety system. Funded by the city of Eugene, the C.A.H.O.O.T.S. program uses a van that is radio-dispatched through the 911 system. A two-person team—a White Bird crisis worker and a trained medic—responds to calls dealing with drug and alcohol abuse, mental illness, emotional crises, and family disputes that pose a small risk of violence.

Over the years, White Bird Clinic’s clientele has also changed, becoming more representative of the mainstream community. The clinic’s crisis intervention team frequently handles calls from area residents of all ages who have questions about personal or family relationships, as well as more serious concerns such as suicide prevention, domestic abuse, or chemical dependency issues. Case in point: Recently, an 11-year-old girl from a middle-class suburb, called the clinic because her parents were going through a divorce, but they weren’t including their daughter in any discussions. The girl was referred to White Bird by a telephone operator. She later talked with a White Bird counselor about what was happening to her and her family.

“Maybe we’re more reputable today than we think we are,” says Bob Dritz, White Bird Clinic’s coordinator, as he reflects on the clinic’s rocky-road history over the last 25 years. It is as if White Bird Clinic has a Protean identity—it continues to evolve and reinvent itself in response to changes in the outside world. Dritz relishes his role as resident historian of White Bird Clinic.

“Maybe we’re more reputable today than we think we are,” says Bob Dritz, White Bird Clinic’s coordinator, as he reflects on the clinic’s rocky-road history over the last 25 years. It is as if White Bird Clinic has a Protean identity—it continues to evolve and reinvent itself in response to changes in the outside world. Dritz relishes his role as resident historian of White Bird Clinic.

With his mop of black hair, tinted aviator-style glasses, and wide-brimmed straw hat, his rag-tag wardrobe, and laid-back crash-pad drawl, Dritz looks and sounds more like a zoned-out, middle-aged hipster than a keen-minded financial whiz who helped guide the clinic down the path to respectability. At the start of each season’s new-volunteer orientation session at White Bird, 20 individuals, who have already been screened by a clinic trainer, sit on the floor in the community room and await their introduction to the organization. Clinic coordinator Dritz sits among the newcomers like a wise tribal chief and recites the oft-told tale of White Bird Clinic.

The history of the clinic dates back to the late 1960s when the drug problem officially hit Eugene, Oregon. Disenchanted, angry, and rebellious youths roamed the streets of this bucolic city nestled in the heart of the lush Willamette Valley in western Oregon. These “hippies,” who had rejected authority and conventional lifestyles, were turning on and tuning in to a new consciousness. They were experimenting with hallucinogens, amphetamines, barbiturates, and just about any other drug they could get their hands on. LSD—”acid”—was the drug of choice for this psychedelic generation who were “tripping” to pursue psychic exploration, achieve satori (enlightenment), or get their kicks on mind-bending, reality-twisting roller-coaster rides.

The problem was that the ticket to nirvana often came at a high price. Young drug users were overdosing, taking bad trips (“bummers”) and “freaking out.” Having severed their ties with straight society, many of the drug-taking youth were without food, shelter, or proper medical care.

In the late sixties, the medical establishment in Eugene and everywhere else didn’t know how to deal with the drug problem. The emergency room doctors were, in the words of one historical account, “flying by the seat of their pants” when treating patients on bad acid trips, injecting them with high doses of phenothiazine tranquilizers, usually 50 mg of Thorazine. Thorazine was seen as a means of normalizing and sedating patients with psychotic or schizophrenic behavior, which is how the ER doctors viewed drug overdoses. The problem was that phenothiazines packed some pretty heavy side effects. A disoriented teenager on a bad trip who came into an emergency room could very well leave in worse shape than when he or she arrived—shot full of Thorazine and now suffering from dizziness, blurred vision, muscle spasms, or tremors.

In the late sixties, the medical establishment in Eugene and everywhere else didn’t know how to deal with the drug problem. The emergency room doctors were, in the words of one historical account, “flying by the seat of their pants” when treating patients on bad acid trips, injecting them with high doses of phenothiazine tranquilizers, usually 50 mg of Thorazine. Thorazine was seen as a means of normalizing and sedating patients with psychotic or schizophrenic behavior, which is how the ER doctors viewed drug overdoses. The problem was that phenothiazines packed some pretty heavy side effects. A disoriented teenager on a bad trip who came into an emergency room could very well leave in worse shape than when he or she arrived—shot full of Thorazine and now suffering from dizziness, blurred vision, muscle spasms, or tremors.

Out of the purple haze that had descended on Eugene, stepped two 25-year-old doctoral students in psychology from the University of Oregon. Dennis Ekanger and Frank Lemons looked like characters from the movie “M.A.S.H:” Here’s Ekanger—a Radar O’Reilly, with more hair. There’s Lemons, a Hawkeye Pierce/Donald Sutherland stand-in, with more hair and a beard, of course.

Ekanger knew firsthand about the problems of drug abuse from his days as a resident hall counselor at the University of Oregon and in his work as a juvenile counselor for the county. The rap on the street was that the chain-smoking, deep-voiced Ekanger was an empathetic guy who could help you cool down and sort things out. Ekanger was living in an old Victorian-style house on 20th Avenue and Lincoln in Eugene’s “student ghetto.” His reputation grew to the point where students and drifters, Vietnam vets and runaways would be hanging out on his doorstep every day wanting to rap about their mixed-up lives.

Like Dennis Ekanger, Frank Lemon had a following. For months, he had been counseling young people in crisis. Lemons’ reputation was enhanced by his counterculture connections. He had many friends living in a large commune on a 200-plus acre farm outside of town. The members of the commune would later form the core group of White Bird’s supervisors and full-time volunteers in the clinic’s early years.

In 1969, Ekanger and Lemons enlisted the support of Dr. Leonard Jacobson, a successful and respected surgeon and past president of the county’s medical society. Dr. Jacobson had been outspoken about the need for new approaches to the drug crisis. He provided the legitimacy and the established community contacts that Ekanger and Lemons lacked.

The three men conceived of a psycho-social-medical approach (influenced by such operations as the Haight Ashbury Free Clinic in San Francisco) and advanced the idea of a community free clinic and counseling/drug education center, a sanctuary to deal with people’s drug-related problems. More than 100 community leaders were involved in the crafting of the proposal for a clinic to be known officially as White Bird Sociomedical Aid Station, Inc.

Ekanger and Lemons each put up $250 to incorporate the clinic and organized a board of directors. The two served as the clinic’s co-directors. After securing grants from the city ($4,800) and state ($7,500), plus community donations, White Bird Clinic started operating on February 22, 1970, in a rented house at 837 Lincoln Street. Furniture was donated by local churches. Area hospitals contributed medical equipment and supplies. In the first few weeks, more than 150 doctors and nurses, plus dozens of attorneys, social workers, and educators donated their time and services to get the clinic up and running. After only one month, the clinic was being used as a field site for graduate students in counseling. Soon, more than 100 -university students were clinic volunteers.

In October 1971, the clinic purchased adjacent houses at 323 and 341 E. 12th Avenue for $67,500. The “annex” at 323 E. 12th housed the medical clinic and drug detox and drug education services. The clinic’s main building at 341 E. 12th was headquarters for crisis intervention, counseling, legal services, and an expanding list of client advocacy and referral programs.

The house at 341 E. 12th Avenue had once been the residence of a prominent physician who was one of the founders of the Eugene Clinic. The house was built for $4,000 in 1917 according to the specifications of Dr. Philip Bartle, a specialist in internal medicine who ran his medical practice on the main floor of the 3,500-square-foot, two-story home where he lived with his -wife and two children.

According to The History of the Willamette Valley, Oregon, published in 1927, Philip Bartle was a perfectionist, “a man among men, possessing a strong and forceful personality.” Bartle was committed to working on behalf of the public welfare for the “betterment of the community along all legitimate lines.” In the 1920s, he helped establish the Eugene Hospital and Clinic, at the time one of only two standardized hospitals in Oregon outside of Portland.

Bartle’s home was designed in the popular craftsman style of his day. This elaborate “bungalow-type” of architecture featured large porches with truncated pillars or columns, low-pitched gable-styled roofs with prominent gabled dormers, and multi-paned windows of varying shapes and sizes. The front room had extensive wood detailing—columns, beams, paneling, and window casements. Two maple window seats flanked the first-floor mantel and fireplace.

Outside, near the top of the front of the house was a decorative swastika. It was removed during World War II. By then, Dr. Bartle had moved, and the house was sold to his son, William and his wife, Mildred. During the late 1930s, several rooms were rented to University of Oregon students, a practice that continued until 1971 when Mildred Bartle sold the house to White Bird Clinic.

Outside, near the top of the front of the house was a decorative swastika. It was removed during World War II. By then, Dr. Bartle had moved, and the house was sold to his son, William and his wife, Mildred. During the late 1930s, several rooms were rented to University of Oregon students, a practice that continued until 1971 when Mildred Bartle sold the house to White Bird Clinic.

The clinic’s operations in the 1970s were a lot shakier than the sturdy structure in which they were housed. By 1972, both Dennis Ekanger and Frank Lemons had resigned. Several White Birders were arrested that year on drug charges; they were later acquitted. In October 1972, the clinic’s medical area was temporarily closed because of lack of supplies, lack of money, and lack of support from the Eugene medical community. The county’s medical society came forward to assist the clinic but told White Bird that it had to clean up its act, raise its standards, and be willing to accept outside advice on all medical matters.

Through all the clinic’s hassles in-the early years, a core of dedicated White Birders served the cause. They staffed the clinic’s drug detox program, continued round-the-clock crisis intervention services, and ran an ambitious drug education program in the community—giving frank talks to area schools, church groups, and civic organizations. They published a “Drug Education Primer,” which was distributed throughout Eugene, and they staged street “guerrilla” theater productions to raise community awareness and show the establishment where the cracks in the medical and mental health systems were.

White Bird’s topsy-turvy operations continued until the late 1970s. A soft-spoken transplanted New Yorker named Bob Dritz arrived in 1978. He became the clinic’s fiscal officer and ushered in a period of maturity and relative calm. In another life, Dritz could have been a CEO of a start-up company and made a small fortune.

White Bird’s topsy-turvy operations continued until the late 1970s. A soft-spoken transplanted New Yorker named Bob Dritz arrived in 1978. He became the clinic’s fiscal officer and ushered in a period of maturity and relative calm. In another life, Dritz could have been a CEO of a start-up company and made a small fortune.

But he used his expertise in fiscal planning and budget management to secure the future of White Bird, not make himself rich. like so many others of his generation, Dritz rejected conventional middle-class values and chose a life of community service and social activism. For his work on behalf of the clinic, Dritz gained near-legendary status. He was proclaimed the “financial savior” of the White Bird Clinic.

In July 1982, Bob Dritz assumed the role of clinic coordinator. At this point, the clinic was being recognized as a legitimate and vital link in the county’s health care system. It had an established crisis counselor training program (the Willamette School of Human Services) licensed by the state of Oregon. The clinic also had a diversified base of funding from local, county, state, and federal grants. By the end of the decade, Dritz would oversee a major expansion and diversification of clinic services.

Today, Bob Dritz talks about how the clinic continues to surprise its critics and leverage its clout as an alternative human service agency.

“We’re willing to take on assignments that no other organization wants or has the ability to perform,” Dritz says, sitting in his office on the second floor of the house with the prominent blue, white and gold bird-in-flight sign hanging above its wide front porch. Throughout its colorful history, the distinctive residence at 341 E. 12th Avenue has undergone many changes and transformations. But after 77 years, it remains a healing house for people in need in Lane County.

Massé has authored three books of literary journalism (“Vietnam Warrior Voices,” “Trauma Journalism” and “Inspired to Serve.”) He is also a novelist, whose latest work, “Honor House,” will be published on Amazon.com in summer 2020. For more information, visit: http://www.markmasse.com

The CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) program began in Eugene in 1989 as a collaboration between the city of Eugene and White Bird Clinic.

CAHOOTS started small: one van equipped with medical supplies and trained personnel, operating part-time in Eugene. Its mission was simple: to offer help to individuals and families, housed and unhoused, in crisis.

The idea was that it would be better — and cheaper — to have people trained and experienced in counseling and medical care to respond to these calls, which had been going to police and fire departments.

The wisdom of that decision has been amply borne out since then by CAHOOTS’ exponential growth over the last three decades and the place it has made for itself in the Eugene-Springfield community.

It has more than tripled its local presence with two vans in Eugene and one in Springfield, and gone from part-time patrols to 24-7 service.

The two-person teams that staff each van respond to an average of about 15 to 16 calls in a 12-hour shift in Eugene, although it can be as many as 25 calls per shift — slightly less in Springfield, CAHOOTS employee Brenton Gicker says, which works out to tens of thousands of calls per year.

Gicker is a registered nurse and emergency medical technician; his partner on a recent night, Maddy Slayden, is a paramedic.

They and their co-workers are a welcome presence on the streets of Eugene-Springfield, greeted with warmth by police officers, with relief by business owners who prefer the option of calling CAHOOTS to calling police, and with respect by the people they help.

CAHOOTS is a significant part of the network of organizations and agencies that provide help to the growing number of people who are homeless locally — about half of CAHOOTS’ calls are to help someone who is homeless, ranging in age from children to seniors.

The CAHOOTS teams have earned respect in the homeless community not just for the help they provide — from distributing socks and bottles of water to emergency medical care and help accessing resources such as medical treatment and emergency shelter — but by the way they do it.

The CAHOOTS employees offer dignity and courtesy, which are often in short supply for people who are homeless.

A typical shift — if there were such a thing — for a CAHOOTS team might include responding to a call about a homeless person disrupting a business; working with a family in crisis; helping someone who is suffering from substance abuse, mental illness or developmental disabilities access services and find safe shelter for the night; treating injuries; picking up people who are being discharged from a hospital or clinic with no place to go and taking them to a safe place where they can get help; and responding to a call from a landlord worried about the welfare of a tenant.

They are trained to address issues such as mental illness or substance abuse and skilled in coaxing people to agree to get the help they need.

Many of their calls involve driving people who are suffering from mental illness or substance abuse to an emergency

room or, if their problem doesn’t merit medical care, to a safe place to spend the night.

Despite more than tripling the size of CAHOOTS in the past few years, the need for its services continues to grow faster than CAHOOTS’ resources.

“I’m frustrated because we can’t be everywhere at once,” Gicker says. “There’s always things we’d like to be involved in, sometimes we don’t have the resources we need, or access to information. I feel like we’re often only scratching the surface.”

CAHOOTS is a uniquely local response to local needs — people familiar with the program say they don’t know of anything quite like it elsewhere.

Its growth in recent years has shown the need for its service; the response within the community, its ability to meet them given the resources.

It’s time to start thinking about expanding a program that has been successful and that serves a need that continues to grow.

Ideally, adding another van would be a step toward meeting this growing need, as well as allowing expansion of service to areas such as Santa Clara and Goshen that have few resources. It also would allow CAHOOTS staff to respond more quickly to calls seeking help, reach more people who are in need of help, and spend more time working to connect people with the resources they need.

It’s hard to put a dollar value on what CAHOOTS does — how do you determine, for example, how many people didn’t die on the streets because of CAHOOTS? How many people who were able to get help that allowed them to stabilize their lives, or medical care that relieved suffering? How do you quantify exactly how much taxpayer money was saved by using CAHOOTS instead of police or firefighters, or the value to businesses of knowing they can call CAHOOTS for help?

But the role the CAHOOTS teams play in Lane County is a critical one, and likely to become even more critical in the coming years.

This editorial is part of a Register-Guard series focusing on productive responses to homelessness reposted with permission from http://registerguard.com/rg/opinion/36272835-78/helping-people-in-crisis.html.csp